1445 words | 7 minute read

Under federal legislation, including the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA, 2015), schools that spend federal funds on literacy programs must establish that there is evidence of effectiveness for those programs. Most educators are interested in doing what works to help students learn to read, but determining an evidence base for what works is not always easy.

There are many different types of research that are conducted to understand literacy. For example, some researchers study cultural practices that influence literacy experiences. Others study the qualities of the teacher-to-student and student-to-student interactions that occur in literacy classrooms. Still others study the kinds of literacy choices students make. All these investigations can provide valuable information and help us understand how individuals’ literate lives are shaped and changed.

Scientific Studies, Evidence-Based Practices, and Related Challenges

However, there is a particular kind of research intended to answer the question of “what works?” We reserve that question for scientific studies that systematically compare the literacy instruction that one group of students receives to an alternative instruction that another group receives. If sufficient numbers of students (or classes) are randomly assigned to the instructional options, it can be classified as an experimental study. Random assignment requires that all participating students have an equal chance of being assigned to the treatment. If students are not randomly assigned, the study is classified as a quasi-experimental study. Scientific research that involves the comparison of literacy programs or practices generate what we refer to as evidence for whether or not the program works. When multiple studies contribute consistently positive results, the instruction that was studied may be considered an evidence-based practice.

Both experimental and quasi-experimental studies can be very difficult to conduct in schools because they involve changing what normally happens in the classroom. They require much stricter adherence to the approaches being studied than we would typically expect of a teacher who was not part of a study, and they require more testing of student performance than we would typically do when not researching their literacy performance. A study also may involve using new programs and practices for a limited period of time. While the research is being conducted and the results determined, the commercial vendors who developed the program may have changed it, making the results less relevant to the new version of the program that a school might purchase. This is particularly true of computer-based programs, which are often updated multiple times throughout a year. Given all of these challenges to conducting scientific research, there may not be evidence available to indicate if a particular program or practice the school is interested in implementing actually “works.”

Determining the Research-Basis in Lieu of Evidence

When there is not available evidence, educators may need to rely on related research that suggests the instructional approach might work. That may take one or more of the following forms:

- Correlation research that establishes there is a relationship between a type of instructional practice and the desired outcome in student performance. Correlation studies do not prove that the practice caused the change in student outcomes—just that there seems to be a relationship of some kind.

- Evaluation research that an organization or vendor conducts to track changes in student performance over a period of time the program is being implemented. Often these organizations or vendors have a vested interest in showing positive results, and they do not customarily follow a rigorous research design. Better designed evaluations may fall into the categories of experimental and quasi-experimental studies. If they do not have a carefully planned comparison group not receiving the program, the studies are not scientific and cannot rule out that students might have improved regardless of receiving that instruction.

- Descriptive research that summarizes the kinds of instruction that are recommended for improving literacy skills. Authors of these reports use existing study results to make the recommendations, but they tend to summarize across practices that they group together as a common type. They do not study a specific program or practice implemented in a systematic way.

- Anecdotal research that explains the experiences of one teacher or school that implemented a program or practice they believed was helpful to their students. This is similar to an evaluation study in that the authors may provide classroom or school data to document students’ improvement, but innovative teachers or schools that are motivated to make changes are likely doing many things that help their students. It could be that no matter what program or practice they tried, they would have worked really hard to ensure students would be successful.

The results from these kinds of studies are what we might refer to as a research basis. There is a rationale for why the instructional approach should work, but there is not strong enough proof yet to have confidence that it will work when a specific variant is implemented in a different place.

Strength of Evidence as Defined in ESSA

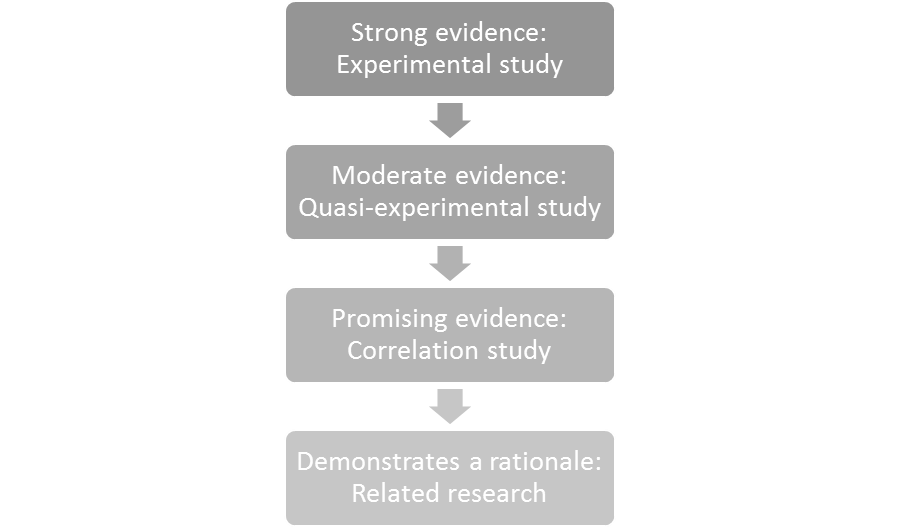

ESSA guidance takes a similar approach to categorizing research by how much confidence we can have in the findings from different kinds of studies (U.S. Department of Education, 2016). Below is a flowchart that indicates how ESSA defines the strength of evidence each study type may generate.

These labels can be somewhat misleading. For example, a literacy program or practice that meets ESSA guidance for having “strong evidence” based on positive findings from one experimental study may not be considered an “evidence-based practice.” For that determination to be made, the program would need each of the following at a minimum:

- Positive results from multiple, rigorously-designed experimental and quasi-experimental studies conducted with large samples of students and across different sites

- No rigorously-designed experimental or quasi-experimental studies with negative results that would override the positive results found by others

- Rigorously-designed experimental or quasi-experimental studies conducted with populations and in settings that are similar to those where the program will be implemented

Effect Sizes and the Measure of Difference Between Approaches

A final area of confusion about a program’s evidence base concerns the effect sizes reported in research or calculated from a school’s own data. An effect size is a means of indicating the size of the difference between the two instructional approaches being compared. This difference may be in assessment scores or other means of evaluating student outcomes. The results of a study may indicate that the students who participated in one program performed statistically significantly better than the students who participated in the alternative program, but the size of that difference may be too small for a teacher to notice in students’ day-to-day literacy work. Effect sizes are expressed in decimals (such as 0.20, 0.73, etc.) and sometimes with whole numbers (such as 1.18, etc.). Generally, larger effect sizes are better than smaller effect sizes, but the values are influenced by many features of a research study. Unexpectedly high effect sizes may be found when a study has one or more of the following characteristics (Cheung and Slavin, 2016; de Boer et al., 2014):

- Small numbers of participating students

- Non-random assignment of students to the instructional approaches being compared

- Locally-developed assessments or assessments that are limited only to the specific items taught

In addition, effect sizes can be calculated in different ways that do not produce the same values. It is really important that educators not search for a particular effect size, such as a “hinge point” or “substantively important” value, without taking into consideration the way the study was designed, the means of measuring students’ performance, and the type of effect size calculated.

Making an Informed Decision About a Literacy Program or Practice

All types of research can help us understand aspects of literacy, but research designs are intended to answer different questions. When we ask questions about what works for helping students become successful readers, we are interested in whether there is a cause-effect relationship between a particular instructional program or practice implemented and students’ subsequent literacy performance. Establishing a causal link requires experimental or quasi-experimental research. To establish an evidence base, federal legislation and regulatory guidance require positive findings from these two study designs. In some cases, correlation research also may be acceptable.

When evaluating any of the available research on a program or practice being considered for implementation, it is important to do a thorough reading of the published reports detailing study results. Do not stop at finding one study with positive results, and do not blindly accept someone else’s summary of what the findings mean. Read the study report carefully to be fully informed about what kind of support it provides, for which students, and under which circumstances. That is the surest way to make an informed decision.

References

Cheung, A. C. K., & Slavin, R. E. (2016). How methodological features affect effect sizes in education. Educational Researcher, 45, 283-292. doi: 10.3102/0013189X16656615

de Boer, H., Donker, A. S., & van der Werf, M. P. C. (2014). Effects of the attributes of educational interventions on students’ academic performance: A meta-analysis. Review of Educational Research, 84, 509-545. doi: 10.3102/0034654314540006

Every Student Succeeds Act, Pub. L. No. 114-95, 20 U.S.C. §6301 et seq. (2015)

US Department of Education. (2016). Non-Regulatory Guidance: Using Evidence to Strengthen Education Investments. Washington, DC. Available from https://www2.ed.gov/policy/elsec/leg/essa/guidanceuseseinvestment.pdf