“Are you gonna take this kid in to get tested or what?”

When Will Caballero was 4 years old, his grandmother, a former special education teacher, asked this of Will’s mother, her daughter, with loving grandmotherly bluntness. She had noticed her grandson’s struggles with several early literacy skills. After Will started preschool, his mother, Megan Caballero of North Liberty, also began to recognize that something was different in the way her youngest child processed language. He was unable to rhyme and was not recognizing any letters. Although it is not uncommon at that age to still be developing those skills, it represented a red flag for Caballero.

In 2014, Caballero decided to take her mother’s advice and seek out a neuropsychological evaluation for Will. At first, evaluators were hesitant to make a diagnosis due to Will’s age. One year later, he was diagnosed with dyslexia.

Defining and Diagnosing Dyslexia

The state of Iowa defines dyslexia as a “deficit in the phonological component of language” that is characterized by “difficulties with accurate and/or fluent word recognition and by poor spelling and decoding abilities.” This learning disability can present itself in elementary-aged students through symptoms such as slow or messy handwriting, choppy and inaccurate reading, and difficulty with spelling, all of which Will was experiencing.

However, even with a formal diagnosis of dyslexia, as well as writing and mathematics learning disabilities, the Caballeros still experienced instances when the seriousness of the disabilities would be misunderstood by some educators.

“I was told to just let him mature, get older,” Caballero said. “And lots of times we were told he just needed to try harder, which was frustrating for both of us.”

The truth is, for students with dyslexia, reading difficulties have nothing to do with a lack of maturity or effort. In actuality, dyslexia is neurobiological in nature. It is caused by physical differences in the way the brain processes information. Students with dyslexia benefit from explicit, systematic, and often multisensory instruction that takes their language processing style into account.

“Students with reading difficulties are usually placed in one reading group, and it doesn’t matter if the student struggles with reading fluency or comprehension,” said Anna Gibbs, Will’s fourth- and fifth-grade special education teacher in the Iowa City Community School District, and former dyslexia specialist at the Iowa Reading Research Center. “But dyslexia is a specific reading disability. It requires a specific type of instruction.”

Addressing Gaps in Dyslexia Knowledge and Training

Dyslexia has been a source of frustration not just for caregivers, but also educators. Educators do not always know how/if they can talk about dyslexia with families and report needing more knowledge and training in how best to meet the needs of students with dyslexia.

But efforts to improve the situation are underway in Iowa. Two years ago, the Iowa Legislature passed and the governor signed into law new dyslexia legislation. Now, most Area Education Agency professionals and elementary educators are required to complete the Iowa Reading Research Center’s eLearning Dyslexia Overview module by July 2024, and all new educators must complete it within a year if they did not already complete it in college. Furthermore, the Dyslexia Specialist Endorsement was established for experienced educators to gain dyslexia expertise by completing the year-and-a-half long program coordinated by the center.

Additionally, the Iowa Department of Education recently outlined priorities for ongoing work to address the needs of students with dyslexia/characteristics of dyslexia. These are highlighted on the Department’s dyslexia website, along with required and recommended responses to dyslexia/characteristics of dyslexia.

“Dyslexia is a type of learning disability,” said Kathy Bertsch, an administrative consultant at the Iowa Department of Education. “While Iowa is a noncategorical state, it doesn’t mean we don’t talk about or recognize dyslexia as a type of learning disability. While educators don’t diagnose dyslexia, the characteristics of dyslexia are important to recognize to be able to talk with families early about possible learning concerns and to collaborate to meet student needs. When we’re more knowledgeable about dyslexia and characteristics of dyslexia, we do better at meeting student needs.”

Finding Support

For Will, a significant amount of instructional support came from a private tutor, Kristen O’Sullivan, who the Caballeros call “Mrs. O.”

“Mrs. O saved our lives,” Caballero said. “She was amazing.”

One particularly successful strategy O’Sullivan introduced was the use of multisensory reading and writing activities. For example, Caballero said Will was much more successful when tracing letters in sand or writing on a material that had a bumpy surface. Multisensory learning—instructional methods that simultaneously activate the parts of the brain that process seeing, hearing, and feeling—can help students with dyslexia learn and remember important literacy skills. Multisensory support can be especially beneficial when integrated into the instructional routines of a structured literacy approach, in which language skills are taught explicitly and directly.

Will also had a teacher dedicated to providing individualized instruction in Melissa Galloway, his fifth-grade teacher at Grant Elementary School in the Iowa City Community School District.

“She just absolutely rocked at making Will feel important, smart, unique,” Caballero said. “For the first time ever, he looked forward to going to school. It really made all the difference.”

According to Caballero, Galloway excelled at designing assignments that played to Will’s strengths.

“She was the one who was receptive to, ‘Okay you don’t want to write a report about this? Make a diorama,’” Caballero said.

While it is not recommended that alternative assignments and other accommodations are used in lieu of structured literacy intervention, it can be important to critically assess the goal of assignments. If an assignment is not meant to explicitly teach writing skills, but rather assess content or concept knowledge and mastery, assigning things such as dioramas, oral reports, or tech-based projects (videos, news reels, etc.) can be a more beneficial and fulfilling means of gauging the content knowledge of students like Will.

Dyslexia-Related Difficulties

In the years since his diagnosis, Will has experienced many successes. However, this journey has not always been easy.

“It was hard on Will because he would have a full day of school and then we would go and have more school when all the other kids were not [doing that],” Caballero said, remembering the days when Will would attend after-school tutoring sessions with O’Sullivan.

In addition to the academic challenges and the associated fatigue, dyslexia can also lead to social and emotional issues for students. Many students with dyslexia also struggle with social isolation, low self-esteem, and higher stress levels. Caballero said for Will, having to leave the classroom for reading interventions or needing to use accommodations that other students do not need has sometimes created feelings of otherness or embarrassment, which is not an uncommon experience for students with learning disabilities.

“He absolutely hated going in front of the class to read,” Caballero said. “He felt like people made fun of him. The emotional aspects of the diagnosis, still to this day, are really hard.”

One way Will’s mother has tried to combat these feelings is by reminding her son that dyslexia is a real learning disability that changes the way his brain functions, not a sign that he is unintelligent or lazy. She also reminds him that dyslexia is not so uncommon; The International Dyslexia Association estimates that dyslexia could affect anywhere from 10–20% of the population, meaning that as many as 1 in every 5 people might experience some form of this disability.

“[I tell him that] his brain just learns differently,” Caballero said. “It doesn’t mean he’s any less smart. His brain just learns differently.”

Becoming an Advocate

Learning disabilities such as dyslexia also have a significant impact on caregivers. As one of these caregivers, Will’s mother has gone above and beyond in becoming an informed advocate for her son.

“As soon as your child gets any kind of diagnosis, you want to learn as much as you can about it,” Caballero said. “You are your child’s best advocate. You have to be persistent and arm yourself for battle, basically.”

Prior to Will’s diagnosis, Caballero said that she knew very little about dyslexia and its effects. In early Individualized Education Program (IEP) meetings following Will’s diagnosis, she remembers feeling as though she did not know what questions to ask.

“I thought what everyone thinks about dyslexia—that people get their numbers and letters reversed,” Caballero said. “So I knew very little, but I quickly made efforts to learn.”

Since then, Caballero has attended trainings and conferences offered by organizations such as Decoding Dyslexia Iowa and has also read several books on the subject.

“You could always tell that Megan did her homework,” Gibbs said, remembering the meetings the two had while Will was her student. “And she had to, in order to advocate for Will.”

Now, Caballero feels confident standing up for Will and helping him receive the support he needs. She remembers one particular meeting in which an educator insisted that Will no longer needed classroom support, as he had received “good enough” scores on that year’s standardized tests. However, Caballero was sure that with the appropriate resources, her son had the capacity to score much higher.

“[They said] this is college path, this is benchmark, and look, here’s Will,” Caballero said. “He’s at benchmark. And I’d go, ‘yeah, but I think he could be college path, if that’s something he chooses to do.’”

Achieving Success

Many brilliant people, including Steven Spielberg, Octavia Butler, and John Lennon, all struggled with dyslexia. In fact, studies show that dyslexia is not just a hindrance to learning; many people with dyslexia also experience common strengths, including strong puzzle solving skills, great spatial reasoning, large imaginations, and more. Will, now an eighth grader, is an outgoing, creative kid with a love for music and football. According to Caballero, he is incredibly funny, a great conversationalist, and a bundle of energy. She cannot help but smile when describing him to others.

“He really does try very hard,” Caballero said. “And he doesn’t want to disappoint others.”

“Anyone who can overcome the struggles Will faced as an early elementary school student has a lot of determination and grit to them,” Gibbs said.

She describes Will as a flexible, hardworking, and determined student who was always ready to show up and do the work. “He was really into football, and he knew he had to practice to get better at that,” Gibbs said. “I think he applied that same thought process to reading.”

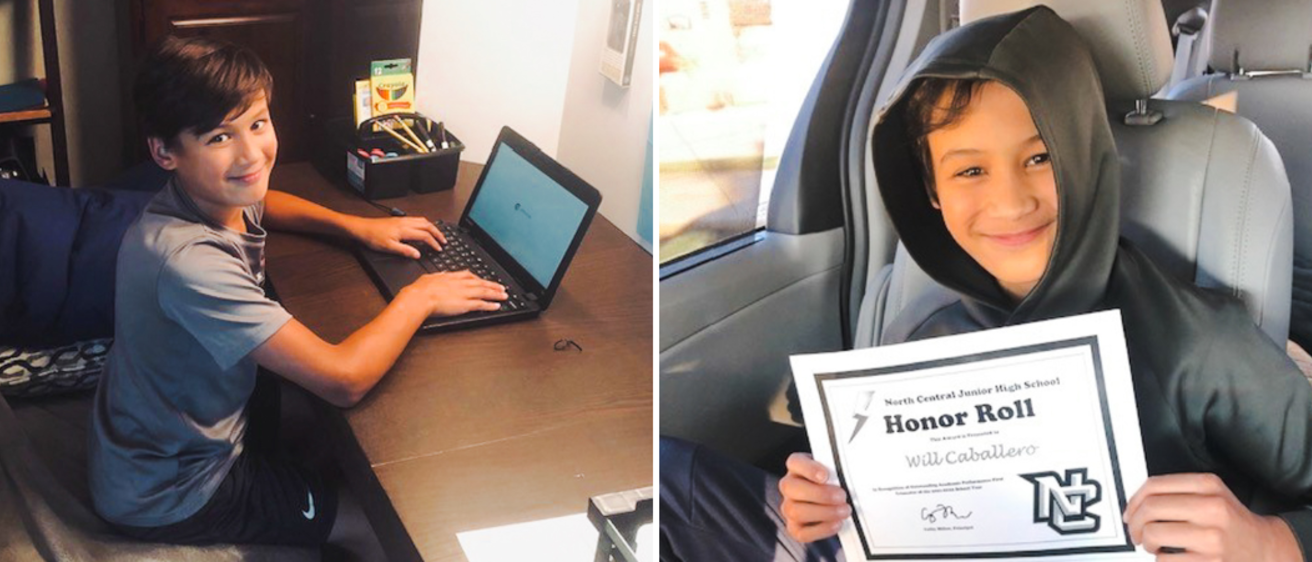

Today, Will is a proficient reader and an outstanding student. In fact, he has made the honor roll every trimester during his time at North Central Junior High in North Liberty.

“You can have dyslexia, and you can be successful,” Gibbs said.

She attributes much of Will’s current success to his ability to independently and consistently utilize the reading skills he has learned, even in new academic environments.

That said, dyslexia is a lifelong condition. Will and other students with this disability will never grow out of it or be cured. However, with the appropriate accommodations and support, students with dyslexia can excel in the classroom and beyond, just as Will has.