1779 words | 9 minute read

Editor's Note: This is the first in a series of blog posts on student-generated higher-order questions that will explain the types of questions that are characterized as higher- and lower-order. We will also provide an instructional sequence for teaching students to classify questions.

Common Core State Standards and Student Questions

In the last decade, states have shifted reading instruction to center on the Common Core State Standards (CCSS; National Governors Association Center for Best Practices & Council of Chief State School Officers, 2010b). The English language arts standards require students from kindergarten to 12th grade to engage in text-based reading, writing, and discussion by asking and answering questions about the text. Although in the primary years, the standards call for students to create questions that clarify explicit meanings of the text, the required complexity of student questions increases as students enter the upper elementary grades. By fourth grade, students must be able to engage in conversations in which they discuss implicit ideas about the text (National Governors Association Center for Best Practices & Council of Chief State School Officers, 2010a). Therefore, students need to learn how to answer and ask higher-order questions to meaningfully engage in discussion activities in a variety of contexts, such as close reading instruction, Socratic seminars, or literature circles.

Higher- Versus Lower-Order Questions

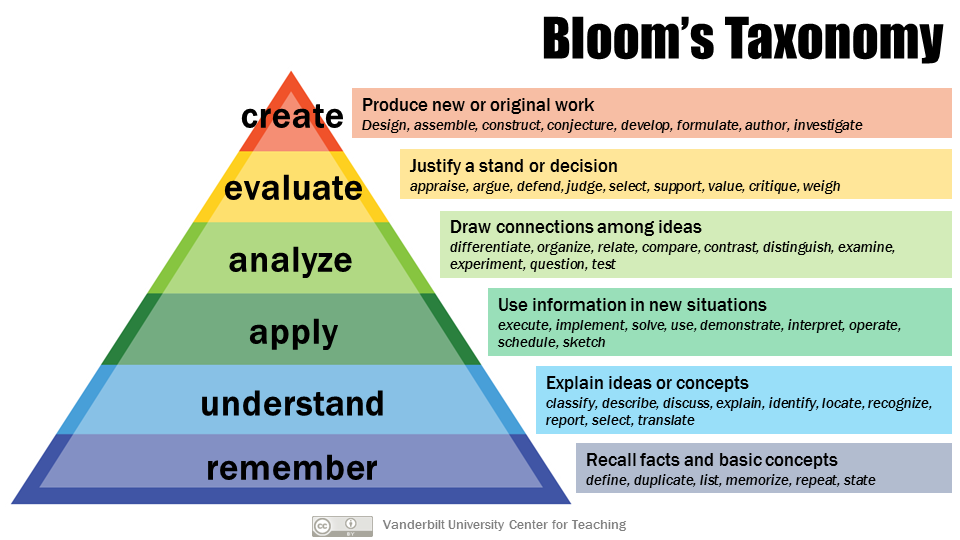

Figure 1. Bloom's Taxonomy

Figure courtesy Vanderbilt University Center for Teaching

Cognition can be divided into a six-tier hierarchy, according to Anderson and Krathwohl’s revision (2001) of a popular educational framework by Benjamin Bloom and coauthors known as Bloom’s Taxonomy (Bloom, Krathwohl, & Masia, 1972). In contrast with Bloom’s original, formally titled “The Taxonomy of Educational Objectives,” the revised taxonomy can be used not only to classify learning goals but also to categorize instructional activities and assessments implemented to meet these objectives (Krathwohl, 2002). Although students’ questions at the lower levels of this taxonomy are important to establish an explicit understanding of texts, instructional time for creating questions should focus on questions that would fall into the three highest levels of this taxonomy.

The following are examples of both higher- and lower-order reading questions, according to the revised Bloom’s Taxonomy. Lois Lowry’s The Giver (1993) is used in these examples, which would be appropriate for a sixth grade English language arts class.

| Sample Questions | ||

|---|---|---|

| Create |

|

Outline Jonas’s plan to leave the community. Then, evaluate the quality of this plan. What are its strengths and weaknesses? Be sure to use textual evidence to support your evaluation.

The Giver explains to Jonas that the community’s Elders changed the structure of society in order to provide people with safety and security. However, some may argue that these new rules were crafted to control, rather than to provide comfort. What do you think influenced the shift in the community? Use textual evidence to support your answer.

In the story, what does Gabriel symbolize?

What motivates Jonas and the Giver to return the memories to the community? Support your answer with textual evidence.

Compare and contrast Jonas and Lily’s points of view regarding the community’s rules.

In The Giver, Jonas is conflicted about his community’s loss of choice. How would you feel if you lived in this community? Would you rather be safe or have the freedom to make decisions? Use textual evidence from the book to support your answer.

Using the Giver and Jonas’s knowledge about Elsewhere, make a prediction about what happens after Jonas rides his bicycle down the hill with Gabriel.

Why is the assignment of Nurturer less prestigious than others?

Summarize Jonas’s first session with The Giver.

In The Giver, to what job was Jonas assigned?

At what age were children given bicycles?

Teaching Students to Classify Questions

The CCSS require students to create their own questions, a skill at the top of the revised Bloom’s Taxonomy. However, before learning this higher-order skill, students must understand how to classify questions as either higher- or lower-order. Below is an instructional sequence for teaching students this skill. The Giver (1993) is again used in this example.

Generate Criteria for Higher-Order Questions

Provide students with examples of higher- and lower-order questions. In pairs or small groups, ask students to try to generate criteria for each type of question and share their ideas with the whole group. For example, students may notice that higher-order questions require implicit knowledge, while lower-order questions can be found directly in the text. They also may notice that higher-order questions require longer responses than lower-level questions, which can be answered with one word, such as “yes” or “no,” or a short phrase. Distribute a checklist (found below in the “Teacher Resource” section) that outlines the criteria for higher-order questions. Refer to this checklist throughout instruction on questioning. Finally, post the image of the revised Bloom’s Taxonomy from from Figure 1 earlier in this post and show students that question complexity increases as they move up the pyramid. Tell them they can use this chart as a resource to develop and evaluate discussion questions.

Question Classification: Modeling

In a think-aloud format, model using the question criteria to classify example questions as higher- or lower-order. Be sure to include at least one example of each. Content below in italics is an example of a teacher think-aloud.

Example Question: In The Giver, to what job was Jonas assigned?

When I read this question, the first thing I will do is try to answer it. When I turn to Page 60 in The Giver (display Page 60 with a document camera or ask students to find that page in their books), I can see that the text directly states Jonas’s assignment (underline the answer in the text). Therefore, the answer to the question is “The Receiver of Memory.”

Then, I will look at the checklist criteria for higher-order questions (display checklist on document camera or anchor chart). I can see that the first criterion is that my answer cannot be found right in the text. I found the answer stated in the text, so the question does not meet this criterion.

Next, I will check my second criterion. It says that the answer to my question cannot be just a few words or phrases. “The Receiver of Memory” is a very short answer to a question. It is not even a complete sentence.

The third criterion is that my question cannot have just one right answer. The only way a person could answer this question correctly is to state that Jonas is The Receiver of Memory.

Finally, I will read the fourth criterion. This one seems to be the trickiest. I can see that whoever is answering the questions should have to think about multiple ideas in the text and use one of the top three levels of thinking of Bloom’s Taxonomy: analyze, evaluate, or create. I am going to decide into which level the question falls (point to Bloom’s Taxonomy anchor chart). I think I will start at the bottom and move up. The “Remember” level says that someone would recall facts or concepts. Answering this question just requires stating that Jonas is The Receiver of Memory. In other words, the answer involves recalling or repeating a fact. This level seems to describe my question.

I can see that I have not checked any of the four criteria for this question (display empty checklist). Therefore, I will classify it as a lower-order question. Although it is a question that could be used to show that my peer understands the text, it will not challenge her to think deeply about the text.

Question Classification: Guided Practice

Provide students with a list of questions. Ask them to work in pairs and use the aforementioned criteria to classify questions as either higher- or lower-order. Tell them that you will be circulating the room to listen to their conversations, and that you want to hear them using the language from the checklist to defend their classifications. Emphasize that they should not try to classify questions based on an initial feeling or reaction. Rather, students should be referring to the information in the text that is needed and explaining how each question meets or does not meet the four criteria. As you circulate the room, engage groups in checklist-based discussions in order to redirect any student misunderstandings.

Question Classification: Independent Practice and Small-Group Discussion

Ask students to independently classify a list of questions as higher- or lower-order. Then, ask them to defend in small groups their classifications by using language from the checklist criteria.

Extension Activity

If students finish early or seem to quickly grasp the difference between the two question types, ask them to revise any lower-order questions to change them to higher-order questions.

Example:

Lower-Order Question: At what age were children given bicycles?

Revision: What does the assignment of bicycles represent in the community? Support your answer with relevant textual evidence.

Student generation of questions has been shown to benefit students in several ways. First, researchers have found student question formulation to have positive effects on reading comprehension (Joseph, Alber-Morgan, Cullen, & Rouse, 2016; Therrien & Hughes, 2008), including in English learner student populations (Taboada, Bianco, & Bowerman, 2012) and those with learning disabilities (Berkeley, Scruggs, & Mastropieri, 2010). However, not all question types have been found to equally affect comprehension. Researchers have concluded that student generation of higher-order questions leads to a higher increase in reading comprehension than when students create questions of a lower order (Taboada & Guthrie, 2006). In addition, when students formulate questions within the context of discussions, their critical thinking skills improve (Abrami et al., 2015). Therefore, in the age of the CCSS, students’ development of higher-order questions can help to improve students’ reading comprehension and ability to speak and write critically about complex texts (Santorini & Belfatti, 2016). Classifying questions is an important skill for students to master before learning to create their own questions. The next post in this series will explain how to teach students to generate higher-order questions.

Check back on the blog Jan. 9, 2018 for the second post on student-generated higher-order questions.

Teacher Resource

The Higher-Order Question Checklist contains four criteria for classifying questions as higher- or lower-order. This resource can be used by both teachers and students.

References

Abrami, P. C., Bernard, R. M., Borokhovski, E., Waddington, D. I., Wade, C. A., & Persson, T. (2015). Strategies for teaching students to think critically: A meta-analysis. Review of Educational Research, 85, 275-314. doi:10.3102/0034654314551063

Anderson, L. W., & Krathwohl, D. R. (2001). A taxonomy for learning, teaching, and assessing: A revision of Bloom's taxonomy of educational objectives. New York: Longman.

Berkeley, S., Scruggs, T. E., and Mastropieri. M. A. (2010). Reading comprehension instruction for students with learning disabilities, 1995-2006: A meta-analysis. Remedial and Special Education, 31, 423-36. doi:10.1177/0741932509355988

Bloom, B.S., Krathwohl, D.R., & Masia, B.B. (1972). Taxonomy of educational objectives: The classification of education goals. New York: David McKay Company.

Fink, L.S. (2017). Literature circles: Getting started. Washington, DC: National Council of Teachers of English. Retrieved from http://www.readwritethink.org/classroom-resources/lesson-plans/literature-circles-getting-started-19.html

Joseph, L. M., Alber-Morgan, S., Cullen, J., & Rouse C. (2016). The effects of self-questioning on reading comprehension: A literature review. Reading & Writing Quarterly, 32, 152-173, doi:10.1080/10573569.2014.891449

Krathwohl, D. R. (2002). A revision of Bloom's taxonomy: An overview. Theory Into Practice, 41, 212-218. doi:10.1207/s15430421tip4104_2

Lowry, L. (1993). The giver. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin.

National Governors Association Center for Best Practices & Council of Chief State School Officers. (2010a). Common core standards for English language arts and literacy in history/social studies, science, and technical subjects. Retrieved from http://www.corestandards.org/assets/CCSSI_ELA%20Standards.pdf

National Governors Association Center for Best Practices & Council of Chief State School Officers. (2010b). Key shifts in English language arts. Retrieved from http://www.corestandards.org/other-resources/key-shifts-in-english-language-arts/

Santorini, D., & Belfatti, M. (2016). Do text-dependent questions need to be teacher-dependent? Close reading from another angle. The Reading Teacher, 70, 649-657. doi:10.10002/trtr.15555

Taboada, A., Bianco, S., & Bowerman, V. (2012). Text-based questioning: A comprehension strategy to build English Language Learners' content knowledge. Literacy Research and Instruction, 51, 87-109, doi:10.1080/19388071.2010.522884

Taboada, A., & Guthrie, J. (2006). Contributions of student questioning and prior knowledge to construction of knowledge from reading information text. Journal of Literacy Research, 38, 1-35. doi:10.1207/s15548430jlr3801_1

Teaching the Core. (2017). Student-led Socratic seminar (Moffat). Retrieved from https://achievethecore.org/page/2982/student-led-socratic-seminar-moffat

Therrien, W. J., & Hughes, C. (2008). Comparison of repeated reading and question generation on students’ reading fluency and comprehension. Learning Disabilities: A Contemporary Journal, 6, 1-16. doi:10.1111/j.1540-5826.2006.00209.x

Vanderbilt University Center for Teaching. (2016). Bloom’s Taxonomy [Infographic]. Retrieved from https://cft.vanderbilt.edu/guides-sub-pages/blooms-taxonomy/