Communication is an essential life skill. Whether you shouted across a crowded room, waved to a friend, or wrote a note to a coworker, you have probably engaged in multiple forms of communication in the last few hours alone. As human beings, we communicate with one another using a vast network of verbal, nonverbal, and written cues, many of which take years of instruction and practice to successfully produce and understand. In order to communicate effectively, traditional language users must be taught to master four primary language skill areas: reading, writing, listening, and speaking. Effective literacy instruction must include explicit instruction in all four of these skill areas (with exceptions for students with certain disabilities; consult with special education instructors for more information).

Categorizing the Four Language Skill Areas

The four language skill areas are interrelated, and a student’s ability in one area can sometimes predict their ability in another. Current neuroscientific research has demonstrated that some of the same parts of the brain are used regardless of which of the four language areas a person is utilizing, suggesting that these skills require the activation of some common brain areas (Berninger et al., 2002). This suggests that developing proficiency in one language skill area could in some ways support the development of another.

However, there are other regions of the brain that only activate during tasks that target the language skill areas individually (Berninger et al., 2002). This means that despite some similarities, each language skill area has its own independent neural function and must therefore be taught and practiced individually. This also indicates that we cannot assume that a student who is proficient in one of the four language skill areas will automatically be proficient in the others. This is especially true for students with reading disabilities. For example, a student with dyslexia may be capable of delivering a complex spoken presentation but struggle to decode basic printed texts. A student with dysgraphia may have trouble spelling but may easily comprehend texts that are well above grade level.

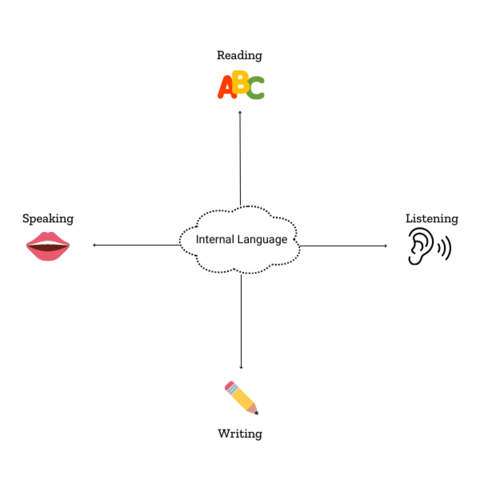

The four language skill areas—reading, writing, listening, and speaking—can be categorized in a few different ways. These categorizations can help us understand the similarities and differences between each of the skills and can also inform our approach to instruction. In the following sections, we will first examine two ways to categorize language skill areas, and then we will explore the kinds of thinking skills used to move from one skill area to another.

Oral Language Skills Versus Written Language Skills

When looking at the four language skill areas, many of us intuitively divide them into these two categories: oral language and written language.

Speaking and listening are oral language skills. While explicit instruction in oral language can help students grow into more talented communicators, most children develop basic oral language skills through exposure to other language users around them, their own thinking skills, and their innate ability (Genishi, 1998).

In contrast, reading and writing are written language skills. Written language is a human invention, rather than a product of natural evolution. In fact, there are many oral languages used by people today that have no written equivalent! Thus, every person must receive explicit instruction in written language skills in order to develop the ability to proficiently encode (translate speech sounds into printed letters) and decode (convert written letters into speech sounds). Evidence tells us that early exposure to oral language can equip children with a foundational understanding of vocabulary, sentence structure, and word patterns that is vital to early literacy learning (Roth et al., 2002). However, explicit instruction that is specific to written language is still necessary for students to become literate.

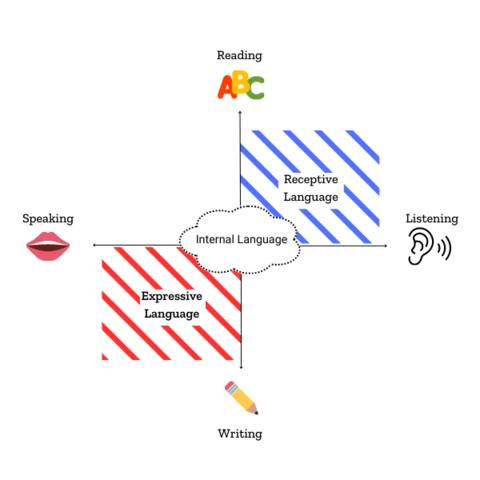

Receptive Language Skills Versus Expressive Language Skills

Despite the differences outlined above, certain oral and written language skills possess important similarities. This is where the categories of receptive and expressive language come into play.

Reading and listening are receptive language skills. They are referred to in this way because students who are proficient in these areas can receive and make meaning from written and spoken communication.

Writing and speaking are expressive language skills, which are sometimes also referred to as “productive skills.” Students who are proficient in expressive skills can generate written and spoken language that effectively communicates meaning.

It is important that literacy instruction requires the use of both expressive and receptive language skills. For example, when learning new vocabulary, it is not sufficient for students to simply read new terms. In order to truly process and retain this new information, students should also practice speaking, hearing, and writing new vocabulary. This same concept applies to all levels of literacy instruction.

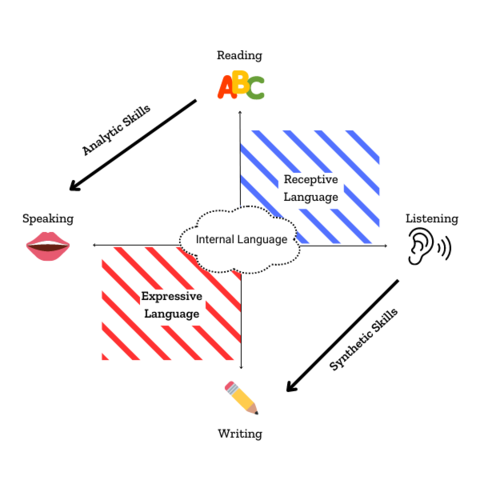

Putting it All Together: Synthetic and Analytic Thinking Skills

As discussed previously, it is important for students to receive explicit instruction specific to each language skill area. However, it is also highly beneficial for students to engage in activities that require them to shift between different skills. Such activities require the activation of either synthetic or analytic thinking skills. These thinking skills are a core component of structured literacy, an approach to literacy instruction that is closely aligned with the science of reading.

Synthetic thinking skills are used to encode, or spell, words by taking small components of language and putting them together. For example, the ability to blend the phonemes /ch/, /o/, and /p/ together to create the written word “chop” is a synthetic thinking skill. Synthetic thinking skills are also used to translate oral receptive language into written expressive language. When students write out the spelling of a word they have heard spoken aloud, they are using synthetic skills to move between language skill areas. First, they hear the word, and then they write it down; in other words, they encode the oral receptive language they have heard as written expressive language on paper.

Analytic thinking skills are the opposite. These skills are used to decode, or read, whole words by breaking them into their component parts. For example, the ability to break the word “chop” into the phonemes /ch/, /o/, and /p/ is an analytic thinking skill. Students can also use analytic thinking skills to translate written receptive language into oral expressive language. When reading a text out loud, students must first read the words on the page, and then pronounce those words out loud; that is to say, they must decode written receptive language and translate it into oral expressive language.

Effective literacy instruction must include both routines that engage synthetic thinking skills and routines that engage analytic thinking skills. Because these activities engage multiple language skill areas, they help students build valuable connections in their brains.

To recap: reading, writing, speaking, and listening are four skills that most individuals use regularly to express and receive language. Reading and writing are written language skills, and listening and speaking are oral language skills.

Writing and speaking are expressive language skills, which we use to produce communication, and listening and reading are receptive language skills, which we use to take in communication.

Synthetic and analytic thinking skills are what we use to move between expressive and receptive language skills. Synthetic thinking occurs when we encode text, or spell, and when we translate oral receptive language into written expressive language. Analytic thinking occurs when we decode text, or read, and when we translate written receptive language into oral expressive language.

Why Synthetic and Analytic Routines Matter

At this point, those of you who are well-versed in structured literacy and the science of reading may be thinking: Where is the evidence? What research do we have showing that this works? These are great questions to ask about any proposed instructional approach, and fortunately, the benefits of synthetic and analytic instructional routines are well documented by years of reading research.

Let us take the example of spelling. Before students can learn to write lengthy essays and reports, they must first learn how to spell. And learning to spell relies on the same foundational awareness of printed and spoken language as is required when learning to read. When instruction leverages this relationship by explicitly teaching students to connect their understanding of spelling (often thought of as a writing skill only) with their understanding of reading—and vice versa—students’ reading proficiency tends to rise (Ehri, 2000). In contrast, when students are taught to read but lack explicit spelling instruction, they are likely to develop into poor readers (Ehri, 2000). The idea that explicit instruction in spelling has a significant impact on writing and reading proficiency has been demonstrated in multiple studies involving elementary and middle-grade students (Graham & Hebert, 2010; Abbott et al., 2010).

The importance of synthetic and analytic instruction, or instruction that includes routines that engage all four language skill areas, is also supported by neuroscientific evidence. As stated previously, the four language skill areas require the use of both common and unique areas of the brain. Additionally, brain imaging research suggests that proficient readers typically demonstrate high levels of interactivity between different parts of the brain when completing language-related tasks (Smith et al., 2018). This suggests that strong readers think multimodally, engaging their understanding of various language skills while reading. This makes sense, as according to many researchers, students’ ability to recognize words automatically relies on their ability to quickly and efficiently map letters to their corresponding sounds (Ehri & Snowling, 2004). This requires a complex understanding of printed letters, speech sounds, and vocabulary, which in turn requires the use of several neural pathways. Practice that engages all four language skill areas encourages the development of these cognitive connections, making students’ word recall faster and more efficient and putting them firmly on the path toward automaticity (Berninger & Wolf, 2016). In other words: “Knowing the spelling of a word makes the representation of it sturdy and accessible for fluent reading” (Snow et al., 2005).

Additionally, reading and spelling activities both require students to engage in repeated practice in identifying common letter-sound patterns. This repeated practice can encourage the development of automaticity in both decoding and encoding abilities (Robbins et al., 2010). Furthermore, students who are strong spellers generally have a well-developed understanding of spelling rules and word parts, such as prefixes, suffixes, and root words (Ehri, 2000). This allows students to develop a more complex vocabulary, which increases their ability to communicate and also increases their access to complex written texts.

That said, while different language skills can support and build off one another, explicit instruction in each individual language area is still vital to student success. Even proficient readers may develop spelling difficulties if they lack practice and support (Mehta et al., 2005). Explicit instruction in all four language skill areas is essential; no one language skill can be expected to make up entirely for another. This is another reason that intentionally engaging both receptive and expressive language skills can be beneficial in the classroom; it prevents any one area of language from being neglected or overlooked.

Practical Application

For Educators

Effective literacy teaching should include instructional routines that engage each of the four language skill areas. For example, emerging readers need explicit instruction in letter-sound correspondences. The development of this ability can be achieved through the use of all four language skill areas. For example, students might be asked to see the letter and say the sound. This is an analytic thinking skill, as it requires students to practice decoding by translating the letter they see (written receptive language skill) to a sound that they can pronounce (oral expressive language skill). To practice letter-sound correspondences synthetically, a teacher might say a sound and then ask students to point to the written letter that makes that sound. This is an example of an encoding. First, students hear a sound (oral receptive language skill), and then they must translate it into its symbolic form (written expressive language skill).

Synthetic and analytic instruction in letter-sound correspondences encourages students to develop a deep understanding of the relationship between letters and sounds. Rather than connecting each letter with a single word, or memorizing catchphrases like “k is for kite,” students are equipped to produce both the oral and written representations associated with each of the 44 phonemes of English.

These same instructional routines can also be implemented during higher-level learning. Students learning a complex vocabulary word like “photosynthesis” will be better equipped to understand and remember that word and its meaning when encouraged to spell it and say it, in addition to reading and hearing it. Vocabulary practice requiring analytic thinking skills might look like seeing a word and pronouncing it out loud, whereas practice requiring synthetic thinking skills might include hearing a word and spelling it on paper. Other activities that engage synthetic and analytic thinking skills could include listening to a story and then writing a response or reading a text and then summarizing it verbally.

Effective literacy teaching must incorporate instances of both synthetic practice and analytic practice at every level of instruction. This should be the case even as the content being taught grows increasingly more complex. To confirm that synthetic and analytic practice opportunities are being incorporated at every level of literacy instruction, educators can refer to the “Synthetic and Analytic Instructional Routines” infographic (see “Supplemental Resources for Teachers and Families”). As a reminder, each concept or skill must be taught to mastery before continuing to more difficult material. For more information on this, see my previous blog post on scope and sequence.

For Caregivers

Caregivers can use their understanding of the four language skill areas to guide at-home practice. For example, if you are working on the letters of the alphabet with your children, teach them to identify and produce both the sounds and written characters associated with each letter. If you have older children and they ask you for the definition of a word you have said, show them what it looks like in writing, encourage them to speak it out loud, repeating after you, and help them spell it out on paper. Like educators, parents may also introduce activities that engage both receptive and expressive language areas. Encourage your children to read aloud to you, ask them to verbally summarize stories they have read, or have them write out the lyrics to songs they like to listen to. For some suggestions of simple, at-home literacy activities that children and teens can do to practice synthetic and analytic thinking skills, see our “7 Ways to Practice Synthetic & Analytic Thinking Skills” guide (see “Supplemental Resources for Teachers and Families”). If you notice that your child is proficient in certain language skills but struggles significantly in others, this may be a sign that they need additional support. In this case, your children’s teachers or your local Area Education Agency (in Iowa) can be excellent resources for further information and assessment.

Supplemental Resources for Teachers and Families

Synthetic and Analytic Instructional Routines

Educators can use this infographic as a reference for how synthetic and analytic instructional routines can be integrated at all levels of literacy instruction.

7 Ways to Practice Synthetic & Analytic Thinking Skills

This resource includes seven examples of activities caregivers can encourage their children and teens to do to practice activating synthetic or analytic thinking skills at home.

References

Abbott, R., Berninger, V. W., & Fayol, M. (2010). Longitudinal relationships of levels of language in writing and between writing and reading in grades 1–7. Journal of Educational Psychology, 102, 281–298. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0019318

Berninger, V. W., Abbott, R. D., Abbott, S. P., Graham, S., & Richards, T. (2002). Writing and reading: Connections between language by hand and language by eye. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 35, 39–56. https://doi.org/10.1177/002221940203500

Berninger, V. W., & Wolf, B. J. (2016). Dyslexia, dysgraphia, OWL LD, and dyscalculia: Lessons from science and teaching (2nd ed.). Paul H. Brookes Publishing Co.

Ehri, L. (2000). Learning to read and learning to spell: Two sides of a coin. Topics in Language Disorders, 20, 19–49. https://doi.org/10.1097/00011363-200020030-00005

Ehri, L., & Snowling, M. J. (2004). Developmental variation in word recognition. In C.A. Stone, E. R. Silliman, B. J. Ehren, and K. Apel (Eds.), Handbook of language and literacy: Development and disorders, (p. 433–460). Guilford Press.

Genishi, C. (1998). Young children's oral language development. ERIC Clearinghouse on Elementary and Early Childhood Education. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED301361.pdf

Graham, S., & Hebert, M. A. (2010). Writing to read: Evidence for how writing can improve reading. Carnegie Corporation of New York. https://www.carnegie.org/publications/writing-to-read-evidence-for-how-writing-can-improve-reading/

Mehta, P., Foorman, B. R., Branum-Martin, L., & Taylor, P. W. (2005). Literacy as a unidimensional construct: Validation, sources of influence, and implications in a longitudinal study in grades 1 to 4. Scientific Studies of Reading, 9, 85–116. https://doi.org/10.1207/s1532799xssr0902_1

Robbins, K. P., Hosp, J. L., Hosp, M. K., & Flynn, L. J. (2010). Assessing specific grapho-phonemic skills in elementary students. Assessment for Effective Intervention, 36, 21–34. https://doi.org/10.1177/153450841037984.

Roth, F. P., Speece, D. L., & Cooper, D. H. (2002). A longitudinal analysis of the connection between oral language and early reading. The Journal of Educational Research, 95, 259–272. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220670209596600

Smith, G. J., Booth, J. R., & McNorgan, C. (2018). Longitudinal task-related functional connectivity changes predict reading development. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 1–13. http://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01754

Snow, C. E., Griffin, P., & Burns, M. S. (Eds.). (2005). Knowledge to support the teaching of reading: Preparing teachers for a changing world. Jossey-Bass.