Editor’s Note: This blog post is part of an ongoing series entitled “Research Briefs.” In these posts, we identify new research studies that are relevant to literacy instruction, summarize their findings, and explain important implications for practitioners.

|

Article Summarized in This Post Roberts, T. A., Vadasy, P. F., & Sanders, E. A. (2019). Preschool instruction in letter names and sounds: Does contextualized or decontextualized instruction matter? Reading Research Quarterly. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1002/rrq.284 |

The alphabetic principle is the understanding that letters are associated with sounds. Along with phonemic awareness, which is the ability to identify and manipulate individual sounds in spoken words, knowledge of the alphabetic principle is an important prerequisite skill for decoding and writing (Caravolas et al., 2001) and a strong predictor of reading achievement later in life (Catts & Tomblin, 2001; Lonigan et al., 2008). Nevertheless, there is limited research on the most effective methods for teaching alphabetic knowledge.

Therefore, a recent study compared the effects of decontextualized and contextualized alphabetic instruction on preschool students’ alphabetic learning (Roberts et al., 2018). Decontextualized alphabetic instruction is an approach that presents letters and sounds in isolation, rather than in a complex context such as connected to the words in a storybook. Conversely, contextualized alphabetic instruction connects letters and sounds to words that are meaningful to students such as children’s names or the representative words and images from a storybook.

Methods

A total of 127 preschool students from five public elementary schools were recruited to participate in this experimental study. Students were randomly assigned to an alphabet intervention either in the decontextualized (64 students) or contextualized (63 students) group. Of the 127 students, 48 were identified as dual-language learners (decontextualized = 26 students; contextualized = 22 students). The intervention sessions were implemented in small groups of three or four students and occurred 4 days per week for 10 weeks. Each session lasted 12-to-15 minutes and was carefully designed to promote explicitly referring to letters and creating opportunities for students to respond. Letters were taught in the following sequence: T, A, D, M, S, H, B, I, F, and K.

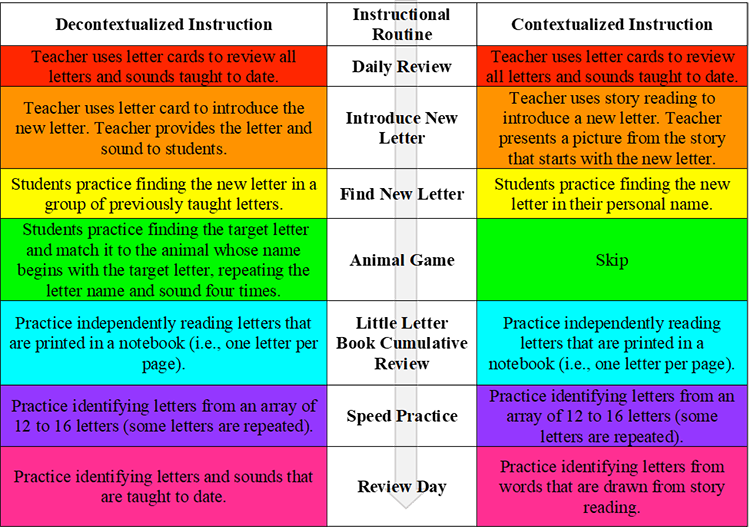

The decontextualized and contextualized instructional routines followed a similar pattern and used simple resources, as described in Figure 1. For example, in both conditions, teachers used letter cards to cumulatively review letters and their sounds, had students independently read letters printed in a notebook, and provided speeded practice identifying particular letters in an array of 12-to-16 letters.

Figure 1. Components of Instructional Routines Used in Decontextualized and Contextualized Alphabetic Instruction

Note. The arrow pointing down in the middle of the figure represents the order of the instructional routine.

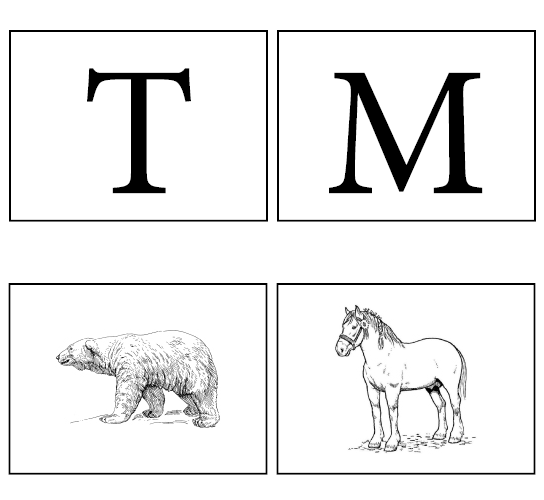

However, there were some notable differences in the instructional components for each condition. Only in contextualized instruction did teachers use stories to introduce new letters and use the names of students in the group to practice finding new letters (e.g., finding “M” in “Melina”). Only in decontextualized instruction did teachers introduce new letters with letter cards and have students identify the first letter and sound when naming pictured animals (see Figure 2 for examples of cards that could be used for this purpose).

Figure 2. Letter and Animal Cards to Teach Students Alphabetic Knowledge

To determine the effects of each instructional condition, the researchers pre- and posttested the preschool students’ alphabetic knowledge, phonemic awareness skills, and language acquisition. All assessments were conducted in English. Alphabetic knowledge was measured with assessments that targeted students’ accuracy and fluency in identifying the letters they had been taught. Letter-name identification accuracy and letter-sound identification accuracy were measured both in isolation and within words that were familiar to students. Students’ fluency identifying the taught letter-names and letter-sounds was measured only in isolation. Phonemic awareness skills were measured by the students’ ability to accurately identify the first sound of a word, which was represented by a picture and stated by the assessor. Finally, the researchers administered two standardized language assessments. One assessment measured receptive vocabulary through identifying a picture that best represented a vocabulary word. The second assessment measured oral language proficiency through answering questions about a story the test administrator read aloud.

Findings

Statistical analysis of the student test data took into account whether or not students were identified as dual-language learners. Results indicated no statistically significant pre- to posttest gains on the two standardized language measures nor in the students’ fluency in identifying taught letter sounds. However, regardless of language status, students in both the decontextualized and contextualized alphabetic instruction groups made statistically significant pre- to posttest gains in accurately identifying taught letter names and sounds and identifying the first sound in a pictured word. Moreover, students in the decontextualized alphabetic instruction group exhibited statistically significant greater gains on their accuracy in identifying the sounds of letters in isolation (effect size of 0.53) and the first sounds of pictured words (effect size of 0.45) compared to students in the contextualized alphabetic instruction group. This effect was not significantly different for students who were and were not dual-language learners. The researchers noted that gains on letter-sound identification were especially important because other studies have found that letter sounds were more difficult to learn than letter names (Boyer & Ehri, 2011; Roberts et al., 2018).

Limitations

Despite the overall gains, researchers identified limitations of this study. First, approximately 30% of students learned fewer than three letter sounds, and 34% of students learned fewer than three letter names. However, students who learned fewer letter names and letter sounds were those who participated in fewer lessons. The second limitation of this study was that researchers did not administer home language assessments, which would have provided richer analysis of dual-language learners’ outcomes.

Practical Implications

Although learning letter sounds is believed to be more challenging than learning letter names (Boyer & Ehri, 2011; Roberts et al., 2018), results of this study revealed that students who were taught the alphabetic principle in isolation made greater gains on tests of letter-sound identification and phonemic awareness than their counterparts who were taught letters in the context of meaningful words from stories and from each other’s names. These findings suggest that preschool students who are and are not dual-language learners can be taught important prerequisite skills for decoding and writing directly and systematically using simple resources.

References

Boyer, N., & Ehri, L. C. (2011). Contribution of phonemic segmentation instruction with letters and articulation pictures to word reading and spelling in beginners. Scientific Studies of Reading, 15, 440–470. https://doi.org/10.1080/10888438.2010.520778

Caravolas, M., Hulme, C., & Snowling, M. J. (2001). The foundations of spelling ability: Evidence from a 3-year longitudinal study. Journal of Memory and Language, 45, 751–774. https://doi.org/10.1006/jmla.2000.2785

Catts, H. W., Fey, M. E., Zhang, X., & Tomblin, J. B. (2001). Estimating the risk of future reading difficulties in kindergarten children. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 32, 38–50. https://doi.org/10.1044/0161-1461(2001/004)

Lonigan, C. J., Schatschneider, C., & Westberg, L. (with the National Early Literacy Panel). (2008). Impact of code-focused interventions on young children's early literacy skills. In National Early Literacy Panel, Developing early literacy: Report of the National Early Literacy Panel (pp. 107–151). https://lincs.ed.gov/publications/pdf/NELPReport09.pdf

Reeger, A. & Aloe, A. M. (2019, November 12). Technically speaking: Why we use random sampling in reading research? Iowa Reading Research Center. https://iowareadingresearch.org/blog/technically-speaking-random-sampling

Roberts, T. A., Vadasy, P. F., & Sanders, E. A. (2018). Preschoolers’ alphabet learning: Letter name and sound instruction, cognitive processes, and English proficiency. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 44, 257–274. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2018.04.011