You see an eye-catching product advertised on television, and you want to order it. If the ad includes a phone number and you remember it long enough to retrieve your phone and dial, you have used working memory. Working memory is the part of one’s memory that temporarily stores small amounts of information needed to perform tasks. In a classroom, if a student is working on a worksheet and a distraction of some sort occurs, working memory guides the student’s attention back to the worksheet once the distraction passes. Our working memory helps us recall what we were doing before the distraction and helps to keep us on task or quickly get us back on task if distracted.

Working memory is a large and complex construct that has been the focus of extensive research. Richard Allen and colleagues (2006) refer to the “Multi-Store Model” of working memory; memory processing that receives both visual and auditory input, retains the information, and processes the information. This involves three components of working memory (Baddeley, 2012; Allen et al., 2006):

- central executive: drives all functions of working memory

- visuospatial sketchpad: stores and processes visual and spatial input

- phonological loop: mentally perceives, stores, and aids in reproduction of the sounds perceived in spoken words or indicated by written letters

The phonological loop component of working memory is commonly referred to as phonological working memory; working memory that allows for processing sounds and then doing something with those sounds such as successfully blending them together to form a word. Phonological working memory supports a variety of skills including vocabulary development, sentence and discourse processing, and acquisition of reading skills (Perrachione et al., 2017).

It is common when evaluating students for language-based learning disabilities (e.g., dyslexia, slow processing speed) to administer assessments of working memory (Gathercole & Pickering, 2000). Working memory can be assessed with tests of recalling digits or lists of words, but evaluating phonological working memory focuses specifically on hearing, retaining, and manipulating different sound units of language. The most common way to assess phonological working memory is by having students repeat nonsense syllables and words that are stated by an examiner. Because pseudo words have no meaning and are not presented in sentences or semantic contexts, students are dependent upon their phonological working memory to learn, discern, or recall the stimulus words. When phonological working memory is weak, it can be very difficult for someone to recall the sounds and syllables heard in the stimulus.

Weak phonological working memory skills can undermine early literacy learning or impede academic progress (Nithart et al., 2010). English is a graphophonemic language. That means it is a combination of graphemes (letters and letter combinations) that represent phonemes (individual sounds) in words. Hence, ensuring that students can discern the phonemes of our language is an important step in early literacy development. Once students can identify the sounds, they then progress to blending, segmenting, manipulating, and associating them with graphemes. This is where a deficit in phonological working memory can erode progress and lead to frustration, anxiety, or compensatory behaviors to avoid relying on the targeted skills (Perrachione et al., 2017). Although compensatory behaviors may give the illusion of success for a limited amount of time, they will ultimately serve to undermine the development of the strong foundational language skills students need for long-term literacy success.

Phonological Working Memory in Application

A weakness in phonological working memory often can be detected in the patterns of errors students make when completing their day-to day literacy work or in their verbal responses during instruction. The following are examples of errors in a phonemic awareness lesson that suggest a possible problem with phonological working memory.

Teacher: (states the following phonemes: /m/ /a/ /p/) Can you blend the phonemes together?

Student 1: Pam.

This could indicate the student can recall the sounds but either does not recall the appropriate order or does not understand the order in which the sounds should be repeated.

Student 2: Ap.

This could indicate the student was not able to hold all three phonemes in phonological working memory and, instead, retained only the last two sounds, /a/ and /p/.

Student 3: Tap.

This could indicate the student recalled that there were three phonemes stated but was unable to recall the correct initial sound. Therefore, they substituted for it with a different sound. These substitutions often will result in a word that is familiar to the student but is not the correct response.

Student 4: Pat.

This could indicate that the student could not recall the appropriate third phoneme or that the student is substituting a familiar word.

Student 5: Truck.

This response could indicate that the student knows to answer with a word but does not have the ability to recall and blend the phonemes stated.

When pictures and supportive contexts are available during reading, students may make errors that appear to be reasonable synonyms or good guesses. For example, a young reader may be asked to decode the word “cat” in a story that also contains an image of a cat. Students may successfully state the sounds /k/ /a/ /t/, but then say the word “kitty.” Although this error does not impact the meaning of the story, it is evidence that the students did not retain the identified sounds in the word “cat” long enough to blend them together and produce the correct word. If caught early, this phonological working memory issue can be addressed to help allow the student to have a more solid foundation for future learning.

Phonological working memory also can be an issue when students have to read more advanced words that require blending together multiple syllables. They may repeatedly omit the first or last syllable. Alternatively, students may guess a longer word because they are unable to remember the syllables to blend and then pronounce them. For example, the student may segment the word “attempt” as /a/ /tempt/ but then blend it back together as “attic” (/a/ /tic/), recalling only the initial /a/ and /t/ phonemes and completing the word with a best-guess attempt.

Instruction to Improve Phonological Working Memory

Just like most other language skills, explicit instruction can improve students’ phonological working memory skills, though in some cases it can take extensive intervention. Initially, intervention might focus only on phonemes, using visuals and manipulatives that do not involve graphemes (Perrachione et al., 2017). To build phonological working memory, the student needs modeling and repeated practice hearing phonemes and remembering them while being asked to manipulate them. The manipulation might involve comparing and contrasting the phonemes, changing their sequence in some way, substituting them with other phonemes, or simply reproducing unfamiliar phonemes on cue. The following examples provide types of activities for building students’ phonemic working memory.

Comparing and Contrasting Phonemes

Teacher: You are going to hear two words, and I want you to tell me if the initial sounds in both of these words are the same or different. The words are “map” and “tap.” Was the first sound the same or different in those two words?

Manipulating Phonemes

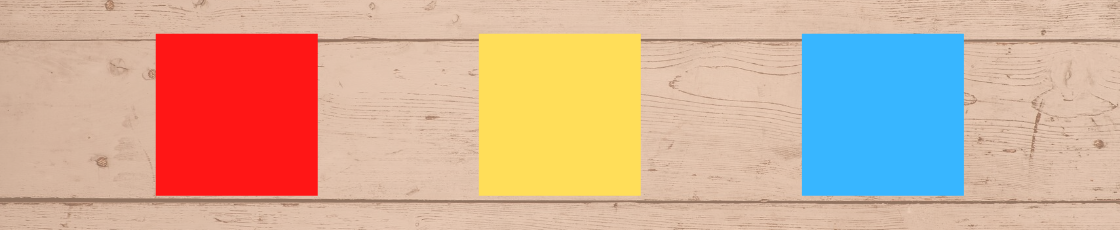

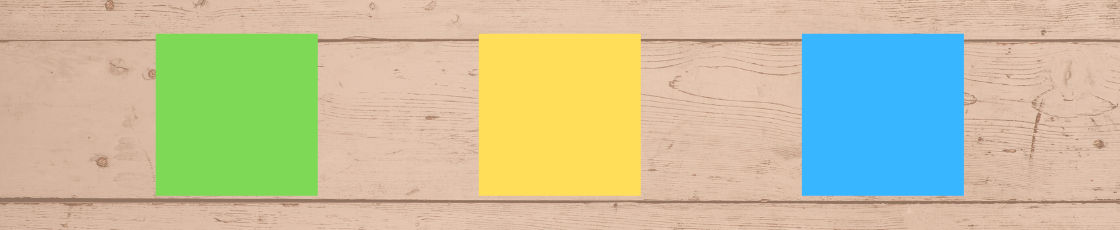

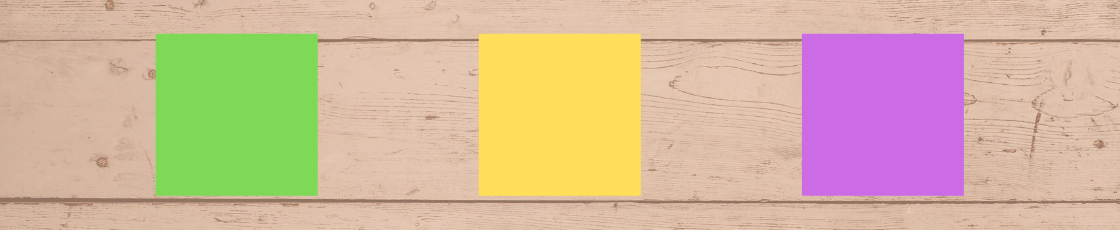

Initial instruction could include an activity involving hearing individual sounds and then blending them together using manipulatives. For example, the teacher can lay different colored blocks representing each different sound of a word out on a table and pronounce the word. The student then can be prompted to pronounce each individual sound while indicating (by touching or tapping) the colored block that represents the sound in the corresponding position in the word. When changing out a sound in the next instructional step, the color tile also should be changed to reinforce the new sound in a multisensory manner.

Teacher: Blend the sounds /b/ /a/ /d/.

Students: Bad.

Teacher: Good! Now, change the first sound in the word “bad” to /m/.

Students: Mad.

Teacher: Correct! Now, change the last sound in “mad” to /p/.

Students: Map.

Eventually, the colored blocks should be withdrawn so that the student is only responding orally.

Repeating Nonsense Words

The students will be listening to, recalling, and audibly repeating nonsense words.

Teacher: I am going to say a made-up or nonsense word. After I say the word, I want you to repeat it as accurately as you can. The word is “nojeap.”

The student should attempt to repeat each word exactly as it is pronounced. Words can progressively increase in number of sounds and syllables as the student’s skills progress.

Most students will develop excellent phonological working memory skills quickly and easily prior to the third grade. For those who do not, identifying and addressing possible phonological working memory issues early may prevent more serious reading and academic difficulties in later grades (Gathercole & Pickering, 2000).

References

Allen, R., Baddeley, A. D., & Hitch, G. J. (2006). Is the binding of visual features in working memory resource-demanding? Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 135, 298–313. https://doi.org/10.1037/0096-3445.135.2.298

Baddeley, A. 2012. Working memory: Theories, models, and controversies. Annual Review of Psychology, 63, 1–29. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-120710-100422

Gathercole, S. E., & Pickering, S. J. (2000). Assessment of working memory in six- and seven-year-old children. Journal of Educational Psychology, 92, 377–390. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.92.2.377

Nithart, C., Demont, E., Metz-Lutz, M. -N., Majerus, S., Poncelet, M., & Leybaert, J. (2010). Early contribution of phonological awareness and later influence of phonological memory throughout reading acquisition. Journal of Research in Reading, 34, 346–363. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9817.2009.01427.x

Perrachione, T. K., Ghosh, S. S., Ostrovskaya, I., Gabrieli, J., & Kovelman, I. (2017). Phonological working memory for words and nonwords in cerebral cortex. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 60, 1959–1979. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5831089/

Quaedflieg, C. W. E. M., Stoffregen, H., Sebalo, I., & Smeets, T. (2019). Stress-induced impairment in goal-directed instrumental behaviour is moderated by baseline working memory. Neurobiology of Learning and Memory, 158, 42–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nlm.2019.01.010