Editor’s Note: This blog post is part of an ongoing series entitled “Effective Literacy Lessons.” In these posts, we provide a brief summary of the research basis for an approach to teaching reading or writing skills, and an example of how a teacher might “think aloud” to model what students should do in completing portions of the lesson. The intent of these posts is to provide teachers a starting point for designing their own effective literacy lessons.

Research Basis

Comprehending texts requires the coordination of multiple skills and can present difficulties to readers of all ages (McKoon & Ratcliff, 2017; Nation, 2019; Potocki, Sanchez, Ecalle, & Magnan, 2017). One method of supporting students in making meaning from text is to teach them how to generate and monitor predictions about what they are going to read (Elbro & Buch-Iversen, 2013; Elleman, 2017). This is a form of inference ability that reflects how a reader is building a mental representation of the text and integrating new information throughout the text to continuously update that mental representation (van den Broek, Beker, & Oudega, 2015).

This post presents an effective literacy lesson for teaching students to make and evaluate predictions to support their comprehension of text.

Lesson Materials

For Teachers:

- Scripted purpose, introduction, and modeling

- Plan for guided and independent practice

- Making and Evaluating Predictions graphic organizer (see Figure 1)

- Text or passage students will read

For Students:

- Making and Evaluating Predictions graphic organizer (see Supplemental Resources for Teachers)

- Text or passage students will read

Instructional Sequence

Lesson Appropriate for Grade 4

For this sequence, a version of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle's short story "The Adventure of the Blue Carbuncle" (1982) retold by Mark Williams (2017) was used. This mystery has been retold for younger audiences by various adapters, and following along with this version by AL Stringer may be helpful in understanding the sequence below. Using a crime story or a mystery to introduce making and evaluating predictions creates natural opportunities to guess which character committed the crime and to update the prediction as suspects are eliminated and new ones introduced. However, students also will need to learn how to make and evaluate predictions for texts of different genres (e.g., comedy, drama, epic, fable, fantasy, historical fiction, science fiction, tragedy).

1. Establish the Purpose

Teacher script: Making predictions is important because it helps us check our understanding of important information while we read. To help us make a prediction, we can use clues, or text evidence, to figure out more about story parts. An inference is based on what readers already know, what they read, and what they observe in story pictures. Readers can use their inferences to make predictions about what might happen next in a story.

2. Introduce the Concept

Teacher script: A prediction is a statement that is a guess. We make predictions about a story when we use information or evidence to guess what kind of story it may be or what may happen in it. When we make a prediction and read further into a story, sometimes we will find new evidence in the text that will show our prediction was correct. Other times, after we make a prediction and read further, we will find new evidence in the text that will show our prediction was incorrect. Evaluating our predictions is an important part of making sure we understand the meaning of the stories we read.

3. Check for Understanding

Teacher script: How can predictions help us?

Possible student responses include:

- They help us pay attention to information while we read.

- They help us look for details in the story.

- They help us check our comprehension of the overall story.

4. Introduce the Graphic Organizer

Project the Making and Evaluating Predictions graphic organizer (see Supplemental Resources for Teachers) on the projection screen.

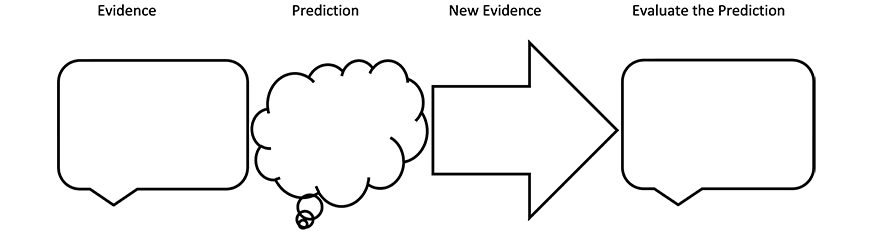

Figure 1. Making and Evaluating Predictions Graphic Organizer

Teacher script: We will be using this graphic organizer to write down and organize our predictions. There are four parts to the organizer. The first box, “Evidence” is where we will write evidence from the story that makes us guess what kind of story it will be or what might happen in it. Next, in the “Prediction” think bubble on the organizer, we will write the prediction. As we read the story, we will use the “New Evidence” arrow on the organizer to keep track of information or new evidence that will help us determine if our prediction was accurate. In the last box, “Evaluate the Prediction,” we will check whether our prediction was correct or incorrect based on the information we gathered while reading. If we think we were right, we will explain why we can confirm the prediction. If we think we were wrong, we will explain why the prediction was incorrect.

5. Model Making a Prediction

Teacher script: I want to make some predictions about this story before I read it. Good readers make predictions and use the information they already know to guess what the story could possibly be about. I am going to start with the title and cover. I see a picture of a man dressed like a detective from long ago, and he is holding something that looks like a magnifying glass. Magnifying glasses might be used by detectives to look for clues to a crime. The title refers to the “adventure,” but it could be an adventure to solve a crime. In the first box on our graphic organizer, I can write my evidence that there is a detective holding a magnifying glass.

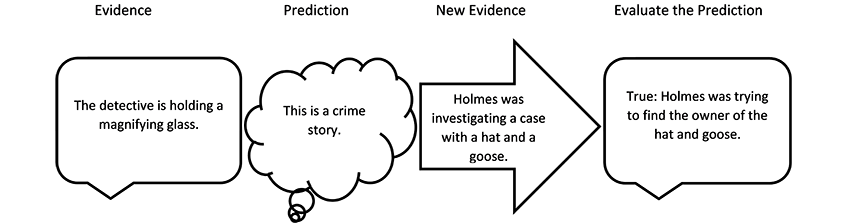

See Figure 2 for an example of how the Making and Evaluating Predictions graphic organizer will be completed during the modeling phase outlined in steps 5 and 6.

Figure 2. Sample for Modeling Use of the Making and Evaluating Predictions Graphic Organizer

Teacher script: I am going to write my prediction in the think bubble of our organizer. My first prediction is going to be about what kind of story we will read so that I know what types of things will happen in the story. I am going to predict that this is a crime story. That means the author will tell me about some crime and how the case of who did the crime was solved. Just like us, the characters will be looking for evidence. The characters’ evidence will be about who is guilty of the crime. Our evidence will be about the predictions we make. Let’s begin reading to look for evidence that will help me evaluate my prediction that this is a crime story. I will be looking for something about solving a crime.

Read the first section of the story aloud or have students read the first section with a partner.

6. Model Evaluating the Prediction

Stop reading after the opening of the story where the case is introduced.

Teacher script: We just read that Holmes was investigating a case with a hat and a goose that had been left behind when a man was attacked. Holmes was using his magnifying glass to study the hat to figure out who owned it. That is information I can include in the arrow on our graphic organizer. The evidence I will write is that Holmes was investigating a case with a hat and a goose. Now I can evaluate my prediction in the last box of our organizer. Holmes is trying to find the owner of the hat and goose because he wants to figure out what really happened. Let’s keep reading to see if we can make another prediction.

Either continue reading aloud or having students read the next section with their partners.

7. Guided Practice Making a Prediction

Stop reading after Holmes learns there was a stolen jewel in the goose.

Teacher script: I think we can use Holmes’ evidence to make a new prediction. Just like Holmes, I want to know who stole that jewel! Who do you think did it? Turn to your shoulder partner and talk about the evidence we learned in the story that can help us guess who stole the jewel.

Listen to student partners talk and find a pair who identify that Henry Baker ran away when the police arrived after he was attacked on the street.

Teacher script: I heard some of you talking about a character in the story who did something that makes him seem guilty. What evidence did we read about a character who might have had something to do with the stolen jewel?

Call on the students who were talking about Henry Baker.

Teacher script: That seems very suspicious, doesn’t it? Why would Henry Baker run away when the police got there? He must have known the jewel was in the goose. Where on our graphic organizer should I write our evidence?

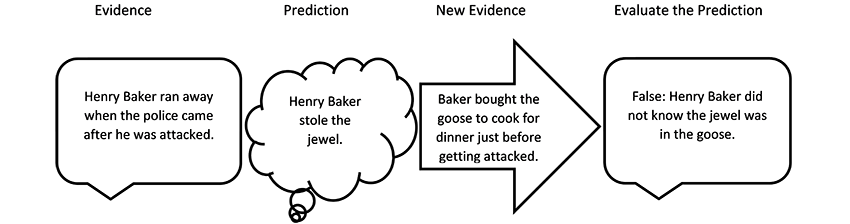

Have students point out the first box. See Figure 3 for an example of how the Making and Evaluating Predictions graphic organizer will be completed during the guided practice phase outlined in steps 7 and 8.

Figure 3. Sample for Guided Practice Using the Making and Evaluating Predictions Graphic Organizer

Teacher script: Who can tell me the prediction I should write in the think bubble on the graphic organizer?

Guide students in developing the prediction: “Henry Baker stole the jewel.”

Teacher script: Let’s keep reading to find evidence for evaluating our prediction.

8. Guided Practice Evaluating the Prediction

Stop after Holmes interviews the goose salesman.

Teacher script: We have read some information that will help us know if our prediction was accurate. Turn to your partner and talk about how you know that Henry Baker did not steal the jewel.

Listen to student partners talk. Find a pair who identifies that Henry Baker bought the goose to cook for dinner just before getting attacked.

Teacher script: I heard some of you talking about what Henry did just before getting attacked. What evidence did you find?

Call on the students who were talking about Henry Baker buying the goose.

Teacher script: Henry Baker ran away after getting attacked because he was scared, not because he was guilty. Where on our graphic organizer should I write our new evidence?

Have students point to the arrow.

Teacher script: Who can tell me what I should write in the last box on the graphic organizer to explain how we know our prediction was incorrect?

Guide students in developing the evaluation: “Henry Baker did not know the jewel was in the goose.”

Teacher script: Let’s keep reading to see if we can make a new prediction about who stole the jewel.

9. Continue Making and Evaluating Predictions in Guided and Independent Practice

For the remainder of the story, continue guiding students in making predictions about who stole the jewel and evaluating the accuracy of their predictions until the crime is solved. On a subsequent day, introduce a new story of a different genre so that students have the opportunity to practice making and evaluating predications with other types of text. If necessary, model the approach with the new genre. Then, ask students to work with a partner to identify evidence, form predictions, identify new evidence, and evaluate the accuracy of their predictions. When students demonstrate 90% or better accuracy on completing the graphic organizers with a partner and while reading a variety of text types, they are ready to make and evaluate predictions independently.

Concluding the Lessons

Each lesson should conclude by reviewing the process and products of students’ work. To provide process feedback, the teacher can ask students to articulate how they noticed textual evidence that made them think of a prediction they wanted to make, or how they knew when they had read evidence that indicated their prediction was correct or incorrect. To provide feedback on students’ graphic organizer products, the teacher might display students’ work and talk about the strengths of what was written in each part or a way to improve how information and predictions are recorded. Ultimately, the lessons should support students’ comprehension of a text, so the focus of the review and feedback should be less on the mechanics and more on improving how students are demonstrating their understanding of what they read.

Supplemental Materials for Teachers

Making and Evaluating Predictions

This graphic organizer helps students write down evidence they find in a text, make a prediction based on that evidence, write down any new evidence they find, and evaluate the prediction they made.

References

Doyle, A. C. (1892). The adventure of the blue carbuncle. In The adventures of Sherlock Holmes. London, England: George Newnes Ltd.

Elbro, C., & Buch-Iversen, I. (2013). Activation of background knowledge for inference making: Effects on reading comprehension. Scientific Studies of Reading, 17, 435-452. doi:10.1080/10888438.2013.774005

Elleman, A. M. (2017). Examining the impact of inference instruction on the literal and inferential comprehension of skilled and less skilled readers: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Educational Psychology, 109, 761–781. doi:10.1037/edu0000180

McKoon, G., & Ratcliff, R. (2017). Adults with poor reading skills and the inferences they make during reading. Scientific Studies of Reading, 21, 292-30. doi:10.1080/10888438.2017.1287188

Nation, K. (2019). Children’s reading difficulties, language, and reflections on the simple view of reading. Australian Journal of Learning Difficulties, 24, 47–73. doi:10.31234/osf.io/gtzqv

Potocki, A., Sanchez, M., Ecalle, J., & Magnan, A. (2017). Linguistic and cognitive profiles of 8- to 15-year-old children with specific reading comprehension difficulties: The role of executive functions. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 50, 128–142. doi:10.1177/0022219415613080

van den Broek, P., Beker, K., & Oudega, M. (2015). Inference generation in text comprehension: Automatic and strategic processes in the construction of a mental representation. In E. J. O’Brien, A. E. Cook, & R. F. Lorch (Eds.), Inferences during reading (pp. 94-121). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Williams, M. (2017). Sherlock Holmes: The blue carbuncle. CreativeSpace Independent Publishing Platform.