Editor’s note: This is the second post in a two-part series on this literacy initiative with the Cedar Rapids Community School District.

In the summer of 2019, the Cedar Rapids Community School District (CRCSD) began working on a project with the Iowa Reading Research Center to improve the literacy abilities of middle school students. Together, CRCSD and the IRRC developed a data-driven instructional cycle in order to improve core literacy instruction in participating schools. At the beginning of the 2019-2020 school year, CRCSD launched the implementation of the cycle in three middle schools.

To find out more about this approach, we caught up with three project leaders: Executive Director of Teaching and Learning John Rice, Executive Director of Middle Level Education Adam Zimmermann, and Middle School Focus Coach Laura Manjooran.

Iowa Reading Research Center (IRRC): What motivated the Cedar Rapids Community School District to Implement a Data-Driven Instructional Cycle in Three Middle Schools?

John Rice, Adam Zimmermann, and Laura Manjooran (collectively referred to as Cedar Rapids Community School District [CRCSD]): Our mission is to ensure every learner has a plan, pathway, and passion for their future. Literacy is fundamental to this mission. Currently, within our middle schools, 66% of middle school students are proficient in the Iowa Core Standards in English Language Arts (ELA). However, when examined by demographic subgroup, we see stark gaps in performance. ELA proficiency rates are 35% for African American students, 20% for students with individualized education programs, and 15% for English learners. In order to improve our literacy outcomes for all of our students, we needed to think differently about our instructional approach, and a data-driven instructional cycle is a key component of that.

In conjunction with our incredibly talented, motivated teachers in CRCSD middle schools, we implemented this cycle to provide the space for our teachers to work together to systematically improve their literacy instruction. Ultimately, we believe this work will lead to improvements in all our students’ literacy skills and outcomes.

IRRC: What Are the Key Components of the Data-Driven Instructional Cycle? Who Is Involved in Implementation?

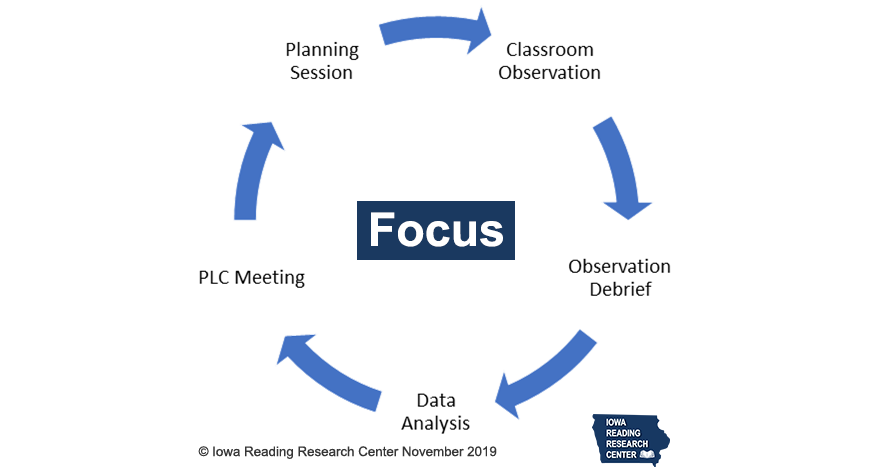

CRCSD: Our program for implementing a data-driven instructional cycle is called “Focus.” This instructional cycle, developed by the Iowa Reading Research Center, is unique in that it incorporates a traditional professional learning community (PLC) approach and one-to-one instructional coaching, centered this year around vocabulary instruction and reading comprehension. The cycle is broken down into five components:

Figure 1. Focus Data-Driven Instructional Cycle

- Classroom observation: Instructional coaches observe general education literacy instruction using our Effective Literacy Practices checklist. These practices outline effective vocabulary and comprehension instruction for adolescents.

- Observation debrief: The teacher and coach meet to debrief the observation and identify next steps for instruction.

- Data analysis: The teacher and coach collaborate to organize students’ formative literacy data. This helps teachers prepare to present their results to their colleagues at the weekly Focus PLC.

- PLC meeting: School teams meet to discuss one teacher’s data and determine next steps for instruction in response to the data. Each teacher is expected to present once every three weeks.

- Planning session: The teacher and coach meet to plan instruction based on the recommendations of the school team.

IRRC: What Has Been Successful so Far in Implementing the Data-Driven Instructional Cycle?

CRCSD: With the help of the IRRC, we have outlined effective literacy instruction for Grades 6-8. Previously, our administrators and teachers did not necessarily agree on what literacy practices were most likely to contribute to students’ success developing their reading and writing skills and using those literacy skills to learn content. We knew what the standards were that students needed to master, but we lacked a shared understanding of the best ways to ensure all students could master them. The IRRC supported us with exploring the key shifts in the standards and identifying evidence-based literacy practices to implement in our classes.

We know that improvement will not be seen overnight. However, we now have a common language to describe effective literacy instruction. This common language is a critical foundation for our work moving forward. Furthermore, our teachers have committed to using rigorous, computer-administered assessments to collect formative literacy data.

IRRC: What Are the Biggest Challenges of Implementing the Data-Driven Instructional Cycle, and How Do You Plan to Address Them?

CRCSD: Two challenges we have faced in our implementation are fidelity to the cycle and integrating new, more rigorous assessments into teaching practice. First, teachers and administrators are wildly stretched for time. The instructional cycle requires teachers, administrators, and instructional coaches to commit to self-improvement and collaborating to help each other improve. A large amount of time must be spent analyzing, discussing, and responding to student literacy data. This involves not only data from teachers’ own students, but also data of colleagues who take turns presenting to the PLC. Too often, these efforts are deprioritized in favor of more immediate concerns such as troubleshooting concerns about student behavior. Yet, we know that in order to improve students’ literacy skills, we must be proactive and use data to plan effective literacy instruction, rather than just react to issues that arise.

Second, related to the focus on analyzing data, we invested in a new screening and progress monitoring assessment system for our middle grades to provide ongoing information about our students’ performance related to reading skills and their progress in mastering grade-level standards. The new computer-based assessments have led to some initial frustration. Teachers and students are not accustomed to technology-enhanced items (e.g., drag-and-drop, multiple select) and rigorous questions. However, when teachers really dig into this data through the instructional cycle, they understand how to implement more rigorous instruction in their classrooms each day. The data inform decisions the coaches and teachers make together about how to plan lessons that target needed skills and move students progressively closer to mastering the standards.

IRRC: What Suggestions Do You Have for Other School Districts Who Are Interested in Implementing a Data-Driven Instructional Cycle?

CRCSD: We recommend that other districts interested in this process give careful consideration to who the right people are to put on your team. We have a great team of teachers and leaders who are committed to improving teaching and learning in their schools. We began by building this group and gaining consensus on the important focus for our efforts.

In addition, our experiences suggest that schools must set aside time for professional learning around instructional practices, mastering the steps in the data-driven instructional cycle, and learning the tools used in the cycle. Everyone involved will need time and learning about the cycle itself before being ready to dig in. We started by working with the IRRC to develop professional learning for our instructional coaches and administrators. The goal of the professional learning was for school leaders to understand the big picture and what their roles would be in implementing the initiative. We followed this with biweekly meetings with the IRRC facilitators, who provide expertise to develop additional professional learning on literacy instruction and help to troubleshoot issues that arise. The ongoing support allows us to improve our ability to lead and support the participating administrators, instructional coaches, and teachers in implementing the steps of the cycle.

Our final recommendation is to maintain fidelity to the instructional cycle. Teachers and administrators are incredibly hard-working and busy. Sometimes self-improvement can slip from the priority list. We had to make sure we had the structure and support in place to monitor and course-correct when needed. For example, the IRRC has helped us develop a fidelity of implementation checklist and prepare our instructional coaches and administrators to observe teachers in classrooms. After an instructional cycle, we use the fidelity data to determine our next steps for professional learning.