Researchers recommend schools adopt Multi-Tiered System of Supports (MTSS) to prevent reading difficulties and support the reading development of PK–12 students (Burns et al., 2016). A critical part of MTSS is the delivery of high-quality, evidence-based literacy instruction to all students—known as Tier 1 or core instruction. Although core instruction is intended to benefit all students, some students, such as those with disabilities, may require additional support. For example, approximately 28% of eighth-grade students without disabilities and 66% of eighth-grade students with disabilities scored below basic on the latest administration of the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) reading assessment in 2024 (NAEP, 2024).

In this post, I briefly describe the evolving nature of MTSS. In addition, I summarize preliminary evidence suggesting classwide interventions—known as Tier 1.5—may strengthen core instruction and benefit student reading development. Finally, I preview an upcoming post and an online application educators can use to determine when Tier 1.5 may be necessary.

What Is MTSS?

Although MTSS and other schoolwide systems, such as Response to Intervention (RTI), are written into federal legislation, their specific components are broadly defined and can vary by state (Berkely et al., 2020). MTSS is briefly defined in federal legislation—specifically, in Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA, 2015), as, “… a comprehensive continuum of evidence-based, systemic practices to support a rapid response to students’ needs, with regular observation to facilitate data-based instructional decision making” (§7801 [33]). Notably, this definition does not prescribe specific instructional approaches or types of decisions to be made. In comparison to legislation, more precise and evolving definitions of MTSS are provided within research.

In research, MTSS components also vary, but they tend to include at least four recommendations (e.g., Fien et al., 2021). First, MTSS includes all students within a school, regardless of age, disability, English language proficiency, or gender.

Second, educators use data from universal screening and progress monitoring assessments to guide instructional decisions. Importantly, student response to reliable and valid assessments drives adjustments to instruction and the provision of intervention.

Third, educators receive professional development that builds their knowledge and skills to deliver evidence-based literacy instruction and intervention.

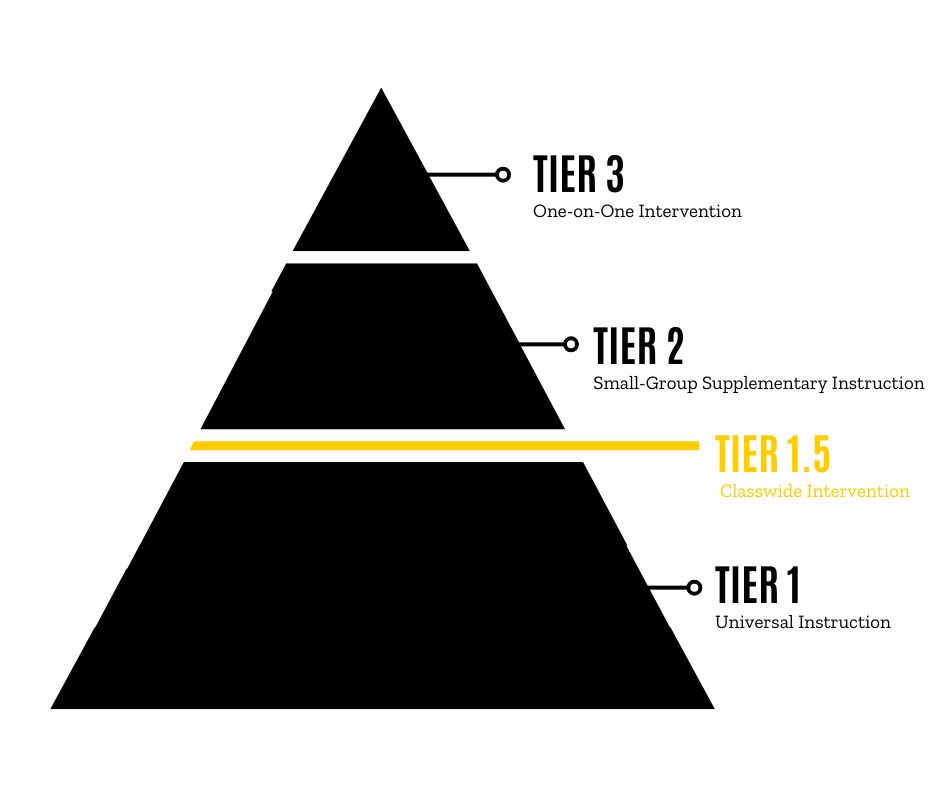

Fourth, schoolwide resources are divided into tiers of support of increasing intensity. Traditionally, there are three tiers of support (Fuchs & Fuchs, 2017). In Tier 1, all students receive high-quality core instruction. In Tier 2, small groups of students who are nonresponsive to core instruction receive additional support. In Tier 3, a small number of students receive highly intensive, personalized instruction.

How Do MTSS Recommendations Evolve?

Although a deep research base underpins each recommended component of MTSS, the recommendations are not static—they change as new research evidence emerges. For example, numerous studies have established the benefits of using curriculum-based measurement (CBM) tasks to inform data-based decision-making and progress monitor response to intervention (Christ et al., 2012); however, precise recommendations on the types and number of CBM tasks to administer have continued to change (e.g., Gesel & Lemons, 2020).

Gradual changes in recommended components of MTSS are likely to continue. Broadly speaking, although each individual component of MTSS is grounded in research, few studies have examined the effects of MTSS as an entire model (e.g., all four MTSS recommendations are embedded within schools and monitored for adherence and quality). Some studies have found positive effects for implementing entire MTSS models—for example, several studies have found student reading outcomes improved with implementing the Enhanced Core Reading Instruction MTSS model (e.g., Fien et al., 2021). Conversely, a large study on MTSS implementation found mixed effects on student outcomes (Balu et al., 2015), but notable limitations in its design and analysis have been noted (Fuchs & Fuchs, 2017).

Where Does Tier 1.5 Fit in MTSS?

One potential beneficial change to MTSS includes increasing the tiers of support. Specifically, some researchers recommended including Tier 1.5 to expand a traditional three-tiered model (Kovaleski et al., 2023). Tier 1.5 refers to additional support provided to all students receiving core instruction through a classwide intervention.

Tier 1.5 supplements traditional three-tier definitions of MTSS by inserting additional support within core instruction. It differs from higher-intensity tiers (i.e., Tiers 2 and 3) by the number of students receiving support. Tier 2 is typically reserved for small groups of students who are nonresponsive to core instruction, and Tier 3 is reserved for individual students who receive personalized, intensive support. Although Tier 1.5 alters the traditional three-tier model of MTSS, the other recommended aspects of MTSS remain the same: All potential students within a school qualify, data-based decision-making is used to determine support, and educators receive professional development on how to implement evidence-based interventions.

As an example of Tier 1.5, one study investigated effects of a classwide intervention on the oral reading fluency of third-grade students (Maki et al., 2022). In the study, data-based decision-making was used to identify classrooms in which the median score of the classroom on universal screeners was below expected criterion. Then, researchers and educators collaborated on professional development to implement a Peer Assisted Learning Strategy (PALS)—paragraph shrinking and partner reading (Fuchs et al., 1997). As a result of the classwide intervention, students who received intervention showed greater gains on their words read correctly per minute compared to students who did not receive intervention.

MTSS is a widely recognized way to structure time, resources, and personnel within schools to improve student reading outcomes. Although there can be differences in how MTSS is defined, one of the primary components tends to be three tiers of support, with core instruction (i.e., Tier 1) provided to all students, then targeted interventions to smaller groups of students (i.e., Tiers 2 and 3). Some preliminary studies suggest that classwide interventions provided to all students during core instruction (i.e., Tier 1.5) can be a source of additional support.

The IRRC is set to publish an accompanying post that will detail how to determine if a Tier 1.5 classwide intervention is needed. It will also include a simple-to-use computer application that allows educators to understand the different decision rules used to determine if a classwide intervention is indeed needed.

References

Balu, R., Zhu, P., Doolittle, F., Schiller, E., Jenkins, J., & Gersten, R. M. (2015). Evaluation of Response to Intervention practices for elementary school reading (NCEE 2016-4000). National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance, Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education. https://ies.ed.gov/ncee/2025/01/20164000es-pdf

Berkeley, S., Scanlon, D., Bailey, T. R., Sutton, J. C., & Sacco, D. M. (2020). A snapshot of RTI implementation a decade later: New picture, same story. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 53(5), 332–342. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022219420915867

Burns, M. K., Jimerson, S. R., VanDerHeyden, A. M., & Deno, S. L. (2016). Toward a unified response-to-intervention model: Multi-tiered systems of support. In S. Jimerson, M. Burns, & A. VanDerHeyden (Eds.), Handbook of response to intervention (pp. 719–732). Springer.

Christ, T. J., Zopluoglu, C., Long, J. D., & Monaghen, B. D. (2012). Curriculum-based measurement of oral reading: Quality of progress monitoring outcomes. Exceptional Children, 78(3), 356–373. https://doi.org/10.1177/001440291207800306

Fien, H., Nelson, N. J., Smolkowski, K., Kosty, D., Pilger, M., Baker, S. K., & Smith, J. L. M. (2021). A conceptual replication study of the enhanced core reading instruction MTSS-Reading model. Exceptional Children, 87(3), 265–288. https://doi.org/10.1177/0014402920953763

Fuchs, D., & Fuchs, L. S. (2017). Critique of the national evaluation of Response to Intervention: A case for simpler frameworks. Exceptional Children, 83(3), 255–268. https://doi.org/10.1177/0014402917693580

Fuchs, D., Fuchs, L. S., Mathes, P. G., & Simmons, D. C. (1997). Peer-assisted learning strategies: Making classrooms more responsive to academic diversity. American Educational Research Journal, 34(1), 174–206. https://doi.org/10.3102/00028312034001174.

Gesel, S. A., & Lemons, C. J. (2020). Comparing schedules of progress monitoring using curriculum-based measurement in reading: A replication study. Exceptional Children, 87(1), 92– 112. https://doi.org/10.1177/0014402920924845

Kovaleski, J. F., VanDerHeyden, A. M., Runge, T. J., Zirkel, P. A., & Shapiro, E. S. (2023). The RTI approach to evaluating learning disabilities (2nd ed.). Guilford Press.

Maki, K. E., Ittner, A., Pulles, S. M., Burns, M. K., Helman, L., & McComas, J. J. (2023). Effects of an abbreviated class-wide reading intervention for students in third grade. Contemporary School Psychology, 26(3), 359–367. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40688-020-00343-4

National Assessment of Educational Progress. (2024). Data tools: NAEP data explorer. The Nation’s Report Card. https://www.nationsreportcard.gov/ndecore/xplore/NDE