1,660 words | 11-minute read

The term “science of reading” refers to accumulated interdisciplinary research evidence describing how individuals learn to read (Petscher et al., 2020). It also refers to the sociocultural movement seeking stronger alignment of reading instruction with evidence-based practices for teaching reading (Duke & Cartwright, 2021). Most states across the U.S. have enacted new legislation mandating use of practices supported by research evidence in school settings (Schwartz, 2025). Many of these policies are multidimensional and include requirements for instructional materials, assessment methods, teacher training and professional development, and teacher certification (Schwartz, 2025). In some states, teachers must pass a reading instruction knowledge test to be eligible to apply for certification (e.g., the Foundations of Reading Test, The Science of Teaching Reading Exam).

As an increasing number of states establish reading knowledge testing requirements, it is important to understand more about teacher knowledge and the assessments used to measure it. In this blog post, I examine: (a) knowledge and skills required for effective teaching, (b) results of studies in which reading knowledge assessments were administered to pre- and in-service teachers, and (c) how teachers’ knowledge relates to their teaching practices and student outcomes.

Note: You can find more information on terminology specific to literacy learning in our reading glossary.

What Content Knowledge and Skills Do Teachers Need to Effectively Teach Reading?

Theories about teacher knowledge offer frameworks for conceptualizing the types of knowledge required for effective teaching. They also highlight the expansive knowledge base needed for effective teaching and the responsibility of teacher preparation programs to impart sufficient knowledge in a relatively short time period (Shulman, 1987).

In many studies of teachers’ reading knowledge, researchers have drawn from Shulman’s theory on teacher knowledge, conceptualizing two main types of teacher knowledge: subject matter content knowledge and pedagogical knowledge. That is, teachers need to know the content they teach and how to teach it.

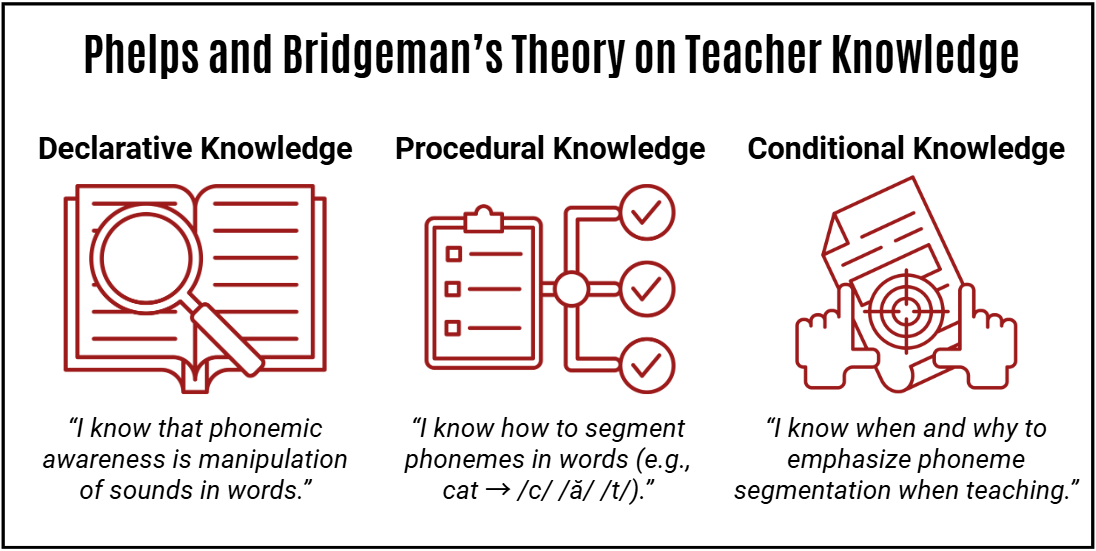

Others have theorized that teachers’ knowledge takes on three forms: declarative (“knowing that”), procedural (“knowing how”), and conditional (“knowing when and why;” Phelps & Bridgeman, 2022, p. 2027). Using phonemic awareness as an example, requisite knowledge may include “knowing that” phonemic awareness is manipulation of individual sounds in spoken words, “knowing how” to segment phonemes in words (e.g., cat → /c/ /ă/ /t/), and “knowing when and why” to emphasize phoneme segmentation when teaching students to spell words (Phelps & Bridgeman, 2022).

Beyond knowledge types, knowledge required for effective reading teaching also spans multiple domains, including, but not limited to, code-focused (i.e., phonological awareness, decoding, sight recognition) and meaning-focused skills (i.e., background knowledge, vocabulary, language structures, verbal reasoning, literacy knowledge; Scarborough, 2001). This knowledge is specialized and extends beyond what may be known by a non-teacher, or simply knowing how to read (e.g., Kucan et al., 2011; Moats, 2020; Phelps, 2009). Scholars have argued that even more specialized knowledge is required when teaching reading to students with reading or writing disabilities (Moats, 2020).

What Are the Average Results of Teacher Reading Knowledge Assessments?

Researchers have conducted many studies of teachers’ reading knowledge, using various assessments (e.g., Binks-Cantrell et al., 2012; Bos et al., 2001; Hall et al., 2024; Kucan et al., 2011). Within this body of research, a large proportion of studies have focused on: (a) elementary pre- and in-service teachers, (b) content knowledge, rather than pedagogical knowledge, and (c) knowledge of language structure (Tortorelli et al., 2021). Most assessments included closed-ended question types (e.g., multiple-choice, matching).

Results of a synthesis of 27 studies examining pre-service teachers’ word reading knowledge indicated that pre-service teachers answered 50–60% of word reading knowledge items correctly, on average (Tortorelli et al., 2021). Notably, pre-service teachers answered phonological knowledge questions (e.g., syllabication) more accurately than phonemic knowledge questions. A similar range of accuracy scores has been reported in various studies measuring in-service general and/or special education teachers’ code-focused content knowledge (e.g., 66.4%, Beachy et al., 2023; 63%, Binks-Cantrell et al., 2012; 60%, Bos et al., 2001; 66%, Lindström et al., 2025; 58%, Porter et al., 2024), with greater mean accuracy scores reported on assessments of meaning-focused knowledge (e.g., 70%, Hudson, 2023).

Researchers have developed many assessments to measure either code- or meaning-focused skills. However, fewer assessments have been designed to assess knowledge of both code- and meaning-focused knowledge. Still, a few have recently been developed. Hall and colleagues (2024) published the Teacher Understanding of Literacy Constructs and Evidence-Based Instructional Practices (TULIP) survey, which assesses knowledge across five domains: (a) phonological awareness, (2) phonics, decoding, and encoding, (3) reading fluency, (d) oral language, and (e) reading comprehension. They administered the TULIP to 313 in-service elementary teachers, most of whom were general education teachers working with Grades K–2 students.

On average, survey respondents answered 50.5% of all items correctly with similar scores across subsets of questions pertaining to each reading domain (range: 44.7–57.9%). Teachers scored lowest on the phonics, decoding, and encoding questions (e.g., What rule informs the use of “ck” in the final position to spell /k/), and they scored highest on reading comprehension questions (e.g., matching comprehension strategies to examples of students’ reading behaviors).

Hall and colleagues also tested relations of reading knowledge (total score and subdomain scores) with teachers’ education level, certification type, teaching position, and grade level band. They reported that teachers’ knowledge was significantly related to their level of education (i.e., high school degree/GED/associates, bachelor’s degree, or master’s degree and beyond). Teachers with more education earned higher overall scores and higher scores for each reading subdomain. This finding regarding education level has not been replicated in some other studies, perhaps due to less variability in respondents’ reported education level in prior studies (e.g., Davis et al., 2022; Jordan et al., 2018, as cited in Hall et al., 2024).

Davis and colleagues (2022) also developed an assessment of both code- and meaning-focused skills and reported that respondents answered meaning-focused questions with greater accuracy than code-focused questions. Notably, their sample included participants working with a wider range of grade levels, including post-secondary instructors.

How Does Teachers’ Reading Knowledge Relate to Teaching Practices and Student Outcomes?

Relative to studies measuring teachers’ reading knowledge, a smaller number of studies have been conducted exploring the relationship between: (a) teachers’ knowledge and instructional practices and (b) teachers’ knowledge and student outcomes.

Hudson and colleagues (2021) reviewed 20 studies reporting on Grades K–5 teachers’ reading knowledge following teacher preparation focused on foundational reading skills. They found that teacher preparation programs had a positive effect on development of phonological awareness, phonics, and morphology content knowledge. In just five of the included studies, student outcomes were also reported. Results of those studies provided preliminary evidence suggesting that students’ word reading outcomes (e.g., word reading fluency) increased as teachers’ knowledge increased.

Examination of a few additional studies provides more insight into how these findings have been replicated across reading subdomains (e.g., phonics, fluency, comprehension). To illustrate, one researcher group provided professional development that addressed evidence-based strategies for teaching code-focused skills to Grades 3–5 teachers of students with learning disabilities (Brownell et al., 2017). Following the intervention, teachers significantly increased their knowledge in some tested subdomains, and teachers’ knowledge significantly predicted students’ word attack and decoding skills.

In a study focused on reading fluency, Park and colleagues (2019) found that special education teachers’ reading fluency knowledge significantly predicted increased students’ oral reading fluency scores. However, teachers’ knowledge (as demonstrated on a quiz) did not predict the instructional practices they were observed using (i.e., number of minutes of instruction, use of research-based practices).

Finally, in a recent meta-analysis of 29 studies of the effects of reading comprehension professional development, Rice and colleagues (2024) found that teachers significantly increased their knowledge following the training, and their knowledge had a small effect on students’ comprehension outcomes. Notably, reading comprehension is a more complex skill to measure (Keenan et al., 2008).

There are also studies in which a significant relation between teacher knowledge and student outcomes has not been substantiated (e.g., Brownell et al., 2009; Carlisle et al., 2011). However, these null results could be due, in part, to less alignment between the measure of teacher knowledge and student outcomes or to the psychometric properties of the assessments (e.g., reliability, validity).

There is still more to discover about the precise knowledge needed for effective reading instruction and how knowledge relates to instructional practice, but there is compelling evidence suggesting teachers’ reading knowledge and student outcomes are related.

Together, the results of the extensive research on teachers’ knowledge of reading suggest that professional development yields increased teacher knowledge which, in turn, predicts students’ reading outcomes to a varying degree across reading subdomains. There is also evidence to suggest that code-focused knowledge may be more difficult for teachers to acquire. Though not discussed in this blog post, teachers’ knowledge of reading assessment, reading development, and learner characteristics (e.g., variation in reading development for children with disabilities) are important considerations within and across reading subdomains.

A coordinated effort is needed to support pre- and in-service teachers in developing requisite knowledge and skills for effective reading instruction. This includes providing resources to help pre-service teachers prepare for licensure examinations focused on reading knowledge. The Iowa Reading Research Center’s “Studying the Science of Reading: Practice Assessment” is a free tool designed to assist with preparation for reading knowledge certification exams, including identifying areas of strength and growth. Questions assess subject matter content knowledge (e.g., What type of morpheme is -ness in the word loneliness?) and pedagogical content knowledge (e.g., Which of the following is the best approach to teaching students the meaning of an idiom?) across nine topic areas, including both code- and meaning-focused skills (e.g., Beginning Reading and Spelling, Reading Comprehension: Informational Texts). Affirmative feedback is provided to deepen knowledge. This tool can also be used by pre-service teacher educators seeking resources to monitor teacher candidates’ skill development across reading domains. Click here to access the IRRC Science of Reading practice assessment.

References

Beachy, R., Guo, D., Wright, K. L., & McTigue, E. M. (2023). The teachers’ perceptions and knowledge of reading assessment survey: A validation study. Reading & Writing Quarterly, 39(6), 559–581. https://doi.org/10.1080/10573569.2022.2156954

Binks-Cantrell, E., Joshi, R. M., & Washburn, E. K. (2012). Validation of an instrument for assessing teacher knowledge of basic language constructs of literacy. Annals of Dyslexia, 62(3), 153–171. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11881-012-0070-8

Bos, C., Mather, N., Dickson, S., Podhajski, B., & Chard, D. (2001). Perceptions and knowledge of preservice and inservice educators about early reading instruction. Annals of Dyslexia, 51, 97–120. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11881-001-0007-0

Brownell, M. T., Kiely, M. T., Haager, D., Boardman, A., Corbett, N., Algina, J., Dingle, M. P., & Urbach, J. (2017). Literacy learning cohorts: Content-focused approach to improving special education teachers’ reading instruction. Exceptional Children, 83(2), 143–164. https://doi.org/10.1177/0014402916671517

Brownell, M. T., Bishop, A. G., Gersten, R., Klingner, J. K., Penfield, R. D., Dimino, J., Haager, D., Menon, S., & Sindelar, P. T. (2009). The role of domain expertise in beginning special education teacher quality. Exceptional Children, 75(4), 391–411. https://doi.org/10.1177/001440290907500401

Carlisle, J. F., Kelcey, B., Rowan, B., & Phelps, G. (2011). Teachers’ knowledge about early reading: Effects on students’ gains in reading achievement. Journal of Research on Educational Effectiveness, 4(4), 289–321. https://doi.org/10.1080/19345747.2010.539297

Davis, D. S., Samuelson, C., Grifenhagen, J., DeIaco, R., & Relyea, J. (2022). Getting KnERDI with language: Examining teachers’ knowledge for enhancing reading development in code‐based and meaning‐based domains. Reading Research Quarterly, 57(3), 781–804. https://doi.org/10.1002/rrq.445

Duke, N. K., & Cartwright, K. B. (2021). The science of reading progresses: Communicating advances beyond the simple view of reading. Reading Research Quarterly, 56(S1). https://doi.org/10.1002/rrq.411

Hall, C., Solari, E. J., Hayes, L., Dahl-Leonard, K., DeCoster, J., Kehoe, K. F., Conner, C. L., Henry, A. R., Demchak, A., Richmond, C. L., & Vargas, I. (2024). Validation of an instrument for assessing elementary-grade educators’ knowledge to teach reading. Reading and Writing, 37(8), 1955–1974. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-023-10456-w

Hudson, A. K. (2023). Upper elementary teachers’ knowledge of reading comprehension, classroom practice, and student’s performance in reading comprehension. Reading Research Quarterly, 58(3), 351–360. https://doi.org/10.1002/rrq.491

Hudson, A. K., Moore, K. A., Han, B., Wee Koh, P., Binks-Cantrell, E., & Malatesha Joshi, R. (2021). Elementary teachers’ knowledge of foundational literacy skills: A critical piece of the puzzle in the science of reading. Reading Research Quarterly, 56(S1). https://doi.org/10.1002/rrq.408

Keenan, J. M., Betjemann, R. S., & Olson, R. K. (2008). Reading comprehension tests vary in the skills they assess: Differential dependence on decoding and oral comprehension. Scientific Studies of Reading, 12(3), 281–300. https://doi.org/10.1080/10888430802132279

Kucan, L., Hapgood, S., & Sullivan Palincsar, A. (2011). Teachers’ specialized knowledge for supporting student comprehension in text-based discussions. The Elementary School Journal, 112(1), 61–82. https://doi.org/10.1086/660689

Lindström, E. R., McFadden, K. A., Fu, Q., & Ruiz, M. J. (2025). Foundational reading knowledge of teachers of students with IDD: Examining experience, degree and time use. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, jir.70041. https://doi.org/10.1111/jir.70041

Moats, L. C. (2020). Speech to print: Language essentials for teachers (3rd ed.). Paul H. Brookes Publishing Co.

Park, Y., Kiely, M. T., Brownell, M. T., & Benedict, A. (2019). Relationships among special education teachers’ knowledge, instructional practice and students’ performance in reading fluency. Learning Disabilities Research & Practice, 34(2), 85–96. https://doi.org/10.1111/ldrp.12193

Petscher, Y., Cabell, S. Q., Catts, H. W., Compton, D. L., Foorman, B. R., Hart, S. A., Lonigan, C. J., Phillips, B. M., Schatschneider, C., Steacy, L. M., Terry, N. P., & Wagner, R. K. (2020). How the science of reading informs 21st‐century education. Reading Research Quarterly, 55(S1). https://doi.org/10.1002/rrq.352

Phelps, G. (2009). Just knowing how to read isn’t enough! Assessing knowledge for teaching reading. Educational Assessment, Evaluation and Accountability, 21(2), 137–154. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11092-009-9070-6

Phelps, G., & Bridgeman, B. (2022). From knowing to doing: Assessing the skills used to teach reading and writing. Reading and Writing, 35(9), 2023–2048. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-022-10278-2

Porter, S. B., Odegard, T. N., Farris, E. A., & Oslund, E. L. (2024). Effects of teacher knowledge of early reading on students’ gains in reading foundational skills and comprehension. Reading and Writing, 37(8), 2007–2023. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-023-10448-w

Rice, M., Lambright, K., & Wijekumar, K. (2024). Professional development in reading comprehension: A meta‐analysis of the effects on teachers and students. Reading Research Quarterly, 59(3), 424–447. https://doi.org/10.1002/rrq.546

Scarborough, H. S. (2001). Connecting early language and literacy to later reading (dis)abilities: Evidence, theory, and practice. In S. B. Neuman & D. K. Dickinson (Eds.), Handbook for research in early literacy (pp. 97–110). The Guilford Press.

Schwartz, S. (2025, July 22). Which states have passed “science of reading” laws? What’s in them? Education Week. https://www.edweek.org/teaching-learning/which-states-have-passed-science-of-reading-laws-whats-in-them/2022/07

Shulman, L. (1987). Knowledge and teaching: Foundations of the new reform. Harvard Educational Review, 57(1), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.17763/haer.57.1.j463w79r56455411

Tortorelli, L. S., Lupo, S. M., & Wheatley, B. C. (2021). Examining teacher preparation for code‐related reading instruction: An integrated literature review. Reading Research Quarterly, 56(S1). https://doi.org/10.1002/rrq.396