Editor’s note: While learning at home, children can make progress toward grade-level reading and writing standards. This post is part of an ongoing series designed to help caregivers support children’s and teens’ literacy learning at home.

An important first step in facilitating children’s literacy learning is to choose high-quality texts related to your state’s standards and aligned to children’s abilities and interests.

Resources for High-Quality Texts for Children

| Resource | Genre | Description |

| CommonLit – Free sign-up & search texts | Literary and informational | Short passages and poems sorted by genre, topic, standard, grade level (Grades 3-12), and Lexile. Available in English and Spanish.

Annotation, translation, and read aloud features available with free student accounts. |

| ReadWorks – Free sign-up & search texts | Literary and informational | Short passages and poems sorted by genre, topic, grade level (Grades K-12), length, and Lexile. Annotation and read-aloud features available with free student accounts. |

| Smithsonian Tween Tribune | Informational | News articles sorted by topic, grade level, and Lexile. Available in English and Spanish. Option to vary Lexile measure of articles. |

| Find a Book | Literary and informational | Tool to identify books matched to children’s and teens’ Lexile measures (which can be estimated). |

| Newsela | Informational | News stories sorted by topic, standard, and Lexile. Option to vary Lexile measure for individual readers. |

Note. Each resource is described in further detail below.

The following content outlines three factors caregivers should consider when selecting texts for children and teens in Grades 3-12 and identifies helpful resources to aid caregivers in this process.

1. Learning Standards

At school, teaching is designed to help students learn specific content and skills, which are outlined in a framework of learning standards. Commonly used frameworks for state literacy standards (such as the Common Core State Standards) divide literacy content and skills into reading, writing, and speaking and listening skills (National Governors Association Center for Best Practices & Council of Chief State School Officers [NGACBP & CCSSO], 2010a). Standards are meant to be mastered over the course of a school year, rather than learned in one day or even over several lessons. Thus, standards can be divided into several subskills, or contributing parts, on which caregivers can focus at home. For example, a standard that calls for students to “determine central ideas or themes of a text and analyze their development; summarize the key supporting details and ideas” (NGABP & CCSSO, 2010a, p. 1) contains several subskills that students may practice at home. Students could practice identifying central ideas, identifying themes, or creating summaries. Practicing a particular skill is made possible by choosing an appropriate text.

Caregivers can use CommonLit (sign up for a free parent account) to search for texts (in English and Spanish) that may be used to practice a chosen standard. In addition, you can filter search results by literary devices (for example, point of view, tone) and genres (for example, drama, legal documents) that would be useful for learning a particular subskill. Another resource, ReadWorks (sign up for a free parent account) offers filtering options for its collection with which caregivers can search for subskills and strategies that might be practiced with texts (for example, identifying explicit ideas, making predictions). Both sites also offer questions children can answer after reading texts. Questions can be chosen based on the standards to which they are aligned.

2. Text Complexity

Current frameworks of literacy standards recommend that students read a range of complex (i.e., challenging) texts (NGACBP & CCSSO, 2010b). All students should have the opportunity to read challenging texts (Lupo et al., 2019), but it is important to choose texts that are accessible enough for them so they can still complete literacy tasks and assignments (Swanson & Wexler, 2017). When selecting texts for children, caregivers can use two indicators of complexity to determine if a text is appropriate: quantitative indicators (usually represented by a numerical measurement) and qualitative indicators (non-numerical qualities or characteristics). One commonly used quantitative indicator is called a Lexile measure (MetaMetrics, 2020). Lexile measures are numerical values used to represent the difficulty of a text as well as children’s reading abilities (Lennon & Burdick, 2014). You or your children might have access to or already know your children’s Lexile measures from reading assessments administered at school. However, if you do not have this information, caregivers can use the Find a Book tool (MetaMetrics, 2020) to estimate their Lexile measures by following these steps:

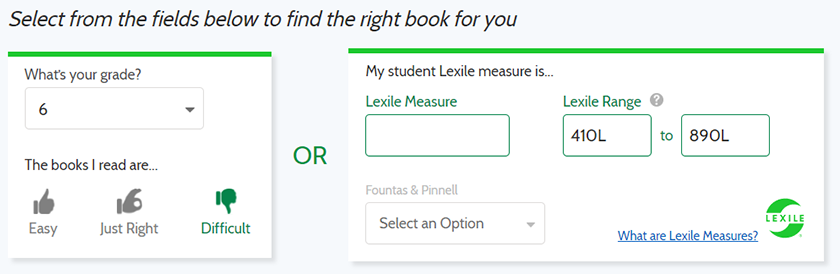

- Under the heading “Select from the fields below to find the right book for you,” select grade in the “What’s your grade?” dropdown menu. In the example above, the child is in Grade 6.

- Below this dropdown, answer “The books I read are…” for your child by clicking “Easy,” “Just Right,” or “Difficult.” In the example above, the caregiver selected “Difficult.”

- After you have made those selections, a Lexile range will be provided to the right of where you made the selections in the “Lexile Range” fields. In our example, the results of “410L to 890L” were provided after the selections were made.

Caregivers can then search or filter texts on any of the sites listed in the Text Selection Resources to find texts that match children’s Lexile measures.

Some challenging characteristics of texts are not captured by quantitative measures of text complexity like Lexile measures (Reed & Kershaw-Herrera, 2016). These qualitative characteristics might include the presence of abstract language in the text, or the need to have large amounts of background knowledge in order to understand the text’s meaning (Pearson & Hiebert, 2013). In addition, the way the text is organized (also known as the text structure) might be especially complicated (Shanahan et al., 2012). Therefore, even if a text is appropriate for a child’s Lexile measure, it is important to read the text and consider whether there are any qualitative characteristics that may limit the child’s ability to access the text.

3. Genre and Topic

Students should be given opportunities to apply the skills and content reflected in a standard to a range of texts (NGACBP & NGSSO, 2010b). So, it is important for caregivers to select texts that reflect a range of genres (such as memoirs, poetry, myths) and topics (such as social issues, sports, elections, technological advances). Additionally, in order to choose texts that will motivate children to do the reading, caregivers should consider children’s interests and whether a topic is culturally relevant to them (Leko et al., 2013). Caregivers can sort texts by genre and topic on CommonLit, Find a Book, and ReadWorks. In addition, Newsela (sign up for a free individual teacher account which is the same account caregivers can use and then search for texts) and Smithsonian Tween Tribune (texts in English and Spanish) offer texts in the genre of news articles and allow users to search by topic.

Supporting children’s progress toward learning literacy standards may seem like a daunting task for caregivers. But by breaking down the critical first step of selecting texts for in-home learning into the three factors described above, caregivers are sure to be successful!

References

Lennon, C. & Burdick, H. (2014). The Lexile Framework as an approach for reading measurement and success. (The Lexile Framework for Reading white paper). Durham, NC: MetaMetrics. http://cdn.lexile.com/cms_page_media/135/The%20Lexile%20Framework%20for%20Reading.pdf

Leko, M. M., Mundy, C. A., Kang, H. -J., & Datar, S. D. (2013). If the book fits: Selecting appropriate texts for adolescents with learning disabilities. Intervention in School and Clinic, 48, 267–275. https://doi.org/10.1177/1053451212472232

Lupo, S. M., Strong, J. Z., & Conradi Smith, K. (2019). “Struggle” is not a bad word: Misconceptions and recommendations about readers struggling with difficult texts. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 62, 551–560. https://doi.org/10.1002/jaal.926

MetaMetrics (2020). Find a book. https://hub.lexile.com/find-a-book/search

National Governors Association Center for Best Practices & Council of Chief State School Officers (2010a). English language arts standards – anchor standards – College and career readiness standards for reading. http://www.corestandards.org/ELA-Literacy/CCRA/R/

National Governors Association Center for Best Practices & Council of Chief State School Officers. (2010b). Key shifts in English language arts. http://www.corestandards.org/other-resources/key-shifts-in-english-language-arts/

Pearson, P. D., & Hiebert, E. H. (August 2013). The state of the field: Qualitative analyses of text complexity. TextProject, Inc. http://textproject.org/researchers/reading-research-report/qualitative-analyses-of-text-complexity/

Reed, D. K., & Kershaw-Herrera, S. (2016). An examination of text complexity as characterized by readability and cohesion. Journal of Experimental Education, 84, 75–97. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220973.2014.963214

Shanahan, T., Fisher, D., & Frey, N. (2012). The challenge of challenging texts. Educational Leadership, 69(6), 58–62. http://www.ascd.org/publications/educational-leadership/mar12/vol69/num06/The-Challenge-of-Challenging-Text.aspx

Swanson, E., & Wexler, J. (2017). Selecting appropriate text for adolescents with disabilities. Teaching Exceptional Children, 49, 160–167. https://doi.org/10.1177/0040059916670630